Friends, in this series, I’m going to attempt an unusual and seemingly challenging task: to describe the business analysis process within an IT project as a usable guide.

It’s unusual because I haven’t seen such a guide in accessible terms and manageable volume. Authors typically like to discuss individual techniques rather than the process as a whole. It’s challenging because, in my opinion, the task is hardly fully achievable. Both points stem from the fact that IT business analysis is a creative kind of wizardry, only loosely susceptible to algorithmization. In other words, it’s not always clear what the final result should look like (the specific business analysis tasks can vary greatly from project to project and company to company), let alone the fact that the set of steps will almost always be unique. Describing the mission as “help the client realize their needs” is difficult to reduce to clear-cut instructions. Nevertheless, I will try — at least for the majority of projects a typical IT specialist encounters.

I should mention that, for example, I once lacked a guide along the lines of “take this as a foundation and then refine it yourself.” The closest thing I found was Karl Wiegers’ Software Requirements, but you had to actively chew through a lot of text. I hope my own vision (based on Mr Wiegers’ work, mixed with cool practices from BABOK, other solid theories, and personal experience) in the form of a concise guide covering typical business analysis stages will help beginners not to get lost and help more experienced folks tune their processes.

It’s unusual because I haven’t seen such a guide in accessible terms and manageable volume. Authors typically like to discuss individual techniques rather than the process as a whole. It’s challenging because, in my opinion, the task is hardly fully achievable. Both points stem from the fact that IT business analysis is a creative kind of wizardry, only loosely susceptible to algorithmization. In other words, it’s not always clear what the final result should look like (the specific business analysis tasks can vary greatly from project to project and company to company), let alone the fact that the set of steps will almost always be unique. Describing the mission as “help the client realize their needs” is difficult to reduce to clear-cut instructions. Nevertheless, I will try — at least for the majority of projects a typical IT specialist encounters.

I should mention that, for example, I once lacked a guide along the lines of “take this as a foundation and then refine it yourself.” The closest thing I found was Karl Wiegers’ Software Requirements, but you had to actively chew through a lot of text. I hope my own vision (based on Mr Wiegers’ work, mixed with cool practices from BABOK, other solid theories, and personal experience) in the form of a concise guide covering typical business analysis stages will help beginners not to get lost and help more experienced folks tune their processes.

Of course, a sea of disclaimers upfront:

1) Describing the entire business analysis process from start to finish is, to put it mildly, a huge task. This guide will be simplified: it won’t cover every type of project, every software development approach (models, methodologies, frameworks, and so forth), every client type and domain, every team context (experience, distribution, etc.), and certainly not every possible scenario (especially those involving a full moon on the fifth month of a leap year).

2) There’s a saying that one of an analyst’s favorite expressions is “it depends.” That is, an analyst is not a role that acts repeatedly by a single algorithm under a clearly defined task. It’s more like a luggage carrier of techniques, from which they craft a specific process adapted to the here and now. But, again, I lacked a base back then to understand how one could even start shaping that final process. I only had a vague idea of where to dig and some clumsy thoughts about first steps. So, here I’ll describe an averaged typical process through my own lens. It can and should be modified by adding mental effort and project context.

3) Everything will be quite simplified. This is not a specification — it’s a quick start guide. Emphasis on what exactly to do and which hammer to pick up. There will be assumptions, simplifications, and scientific precision will definitely suffer. The full books polishing this foundation have already been written by Mr Karl and other great specialists.

1) Describing the entire business analysis process from start to finish is, to put it mildly, a huge task. This guide will be simplified: it won’t cover every type of project, every software development approach (models, methodologies, frameworks, and so forth), every client type and domain, every team context (experience, distribution, etc.), and certainly not every possible scenario (especially those involving a full moon on the fifth month of a leap year).

2) There’s a saying that one of an analyst’s favorite expressions is “it depends.” That is, an analyst is not a role that acts repeatedly by a single algorithm under a clearly defined task. It’s more like a luggage carrier of techniques, from which they craft a specific process adapted to the here and now. But, again, I lacked a base back then to understand how one could even start shaping that final process. I only had a vague idea of where to dig and some clumsy thoughts about first steps. So, here I’ll describe an averaged typical process through my own lens. It can and should be modified by adding mental effort and project context.

3) Everything will be quite simplified. This is not a specification — it’s a quick start guide. Emphasis on what exactly to do and which hammer to pick up. There will be assumptions, simplifications, and scientific precision will definitely suffer. The full books polishing this foundation have already been written by Mr Karl and other great specialists.

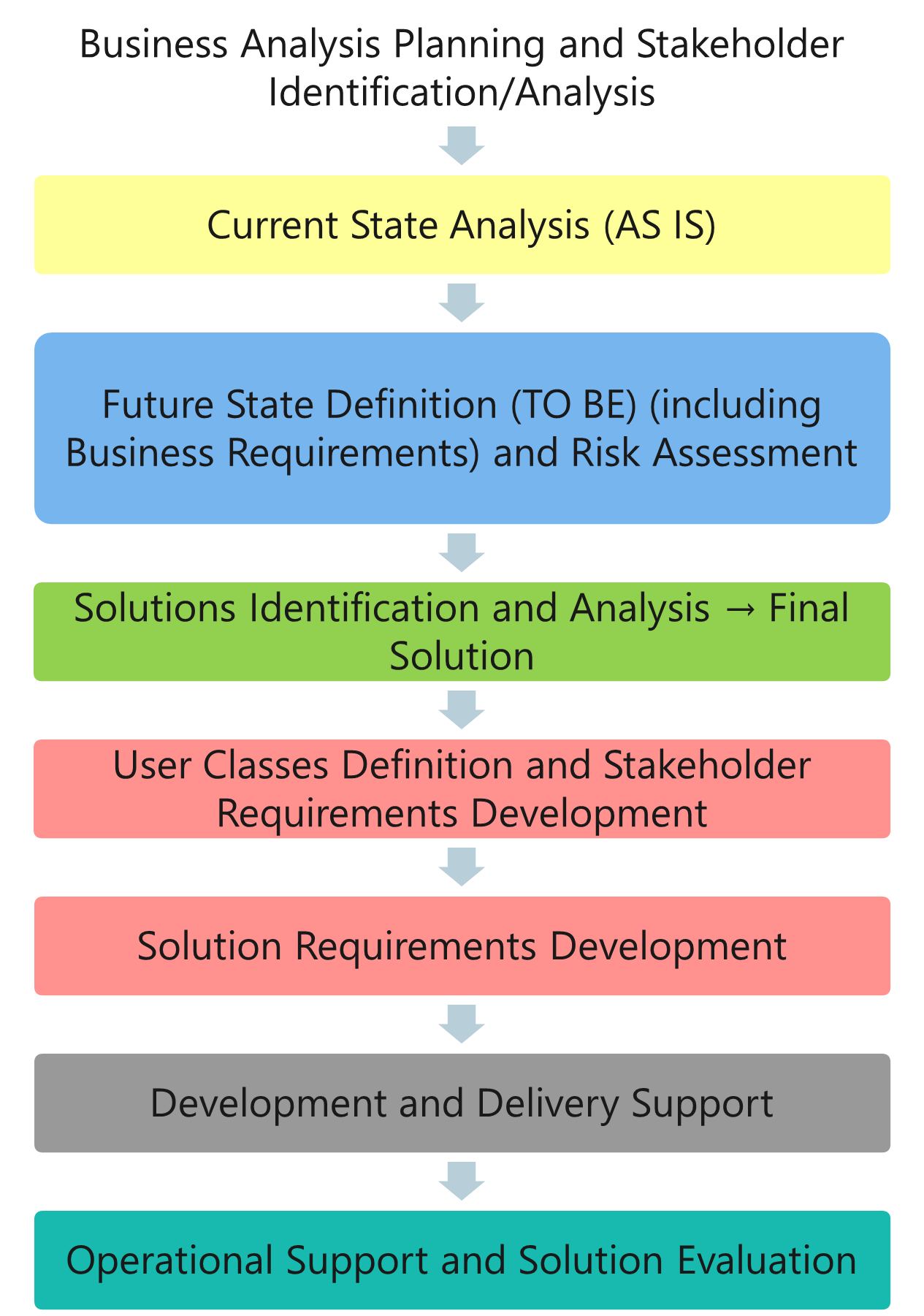

To start, the business analysis process in IT projects looks like this:

In general, this is the process a spherical-in-a-vacuum business analyst needs to go through on a project to bring happiness to all stakeholders. That is, take these stages, reflect on their relevance and specifics for your current project, and get to work. Here’s the essence of each stage (we’ll discuss them in detail in future posts):

Business Analysis Planning and Stakeholder Identification/Analysis.

Conceptually, this is simple. Like any project activity (and business analysis is a mini-project, yes), first you need to think about how, when, what, with whom, and for what you will do. You can try to painstakingly design a plan as reliable as Swiss watches, or accept the uncertainty of our creative work and focus only on the near future. We’ll talk about details later, but the main points to consider are:

This is not exhaustive but key. It’s important to understand: this scheme is not a waterfall (i.e., not a rigid sequence). Some might already be wondering how you can plan all this when you know nothing about the project yet. Right, you probably can’t build decent plans at this point. Plans will evolve as the information fog clears. At best, you can make rough hypotheses at the start. Then, as you gain more understanding of your place in the project, you’ll update and refine your plans. Conceptually, planning happens at the start, but a) detail and accuracy may be near zero at this stage, and b) you need to keep revising plans over time (so this stage is actually spread throughout your project activity).

Conceptually, this is simple. Like any project activity (and business analysis is a mini-project, yes), first you need to think about how, when, what, with whom, and for what you will do. You can try to painstakingly design a plan as reliable as Swiss watches, or accept the uncertainty of our creative work and focus only on the near future. We’ll talk about details later, but the main points to consider are:

- The overall business analysis approach: formal-detailed-long VS flexible-superficial-simple, or more waterfall-like VS agile (ideally a reasonable combo)

- What artifacts (documents, prototypes, models, etc.) you plan to produce

- What tasks need to be done (who, when, in what order) and the visible risks upfront

- Who are your stakeholders, their important traits, and how you plan to interact with them to get your job done

- How you will organize the useful information you gather and accumulate

This is not exhaustive but key. It’s important to understand: this scheme is not a waterfall (i.e., not a rigid sequence). Some might already be wondering how you can plan all this when you know nothing about the project yet. Right, you probably can’t build decent plans at this point. Plans will evolve as the information fog clears. At best, you can make rough hypotheses at the start. Then, as you gain more understanding of your place in the project, you’ll update and refine your plans. Conceptually, planning happens at the start, but a) detail and accuracy may be near zero at this stage, and b) you need to keep revising plans over time (so this stage is actually spread throughout your project activity).

The next three stages are the strategy analysis phase, aka discovery. Here, we need to understand what and why our team will do on the project overall.

Current State Analysis (AS IS) — understand what problems or opportunities led the client to request software development or any other service that brought us here (developing a new product, enhancing something existing, supporting a live system in production, etc.). This requires immersing ourselves in the client’s domain and activities.

Future State Definition (TO BE) — understand where the client (the money-payer) wants to get. Here we work out business requirements and other key details clarifying them. This is necessary to understand the overall impact the client expects from the initiative and the strategy to achieve it.

Solutions Identification and Analysis, and Definition of the Final Solution and Its Scope — here, together with the client and other key people, we think about which solution will most effectively bring us to the future state. That is, from “where” we want to go (step 3) we move to “how” we will get there. We need to decide what the development team’s focus will be (web app, mobile app, complex combo of business process improvements plus multiple software systems, enhancements to an existing system, buying and configuring an off-the-shelf product, etc.). This solution and the broad outline of its scope will guide all further steps. Scope definition can be tough to do purely with the client — you might need to check with users (next step) at least briefly.

It’s important to assess whether this whole phase is relevant for your project. Its appropriateness is often questionable. It depends on the service level your company provides, project type and your role, work already done without you, and the client’s motives. For example:

- For a typical outsourcing developer whose job is just to implement client requests without poking into strategy, this phase might be unnecessary.

- For a product with strategists (not you), your role might be to humbly elaborate on requirements for a solution smart people have already decided on.

- Sometimes pre-sale has already covered this (maybe not perfectly), and you just need to deliver what was promised on schedule.

- Even if the company and project value these activities, the client might dislike spending precious developer hours on this, expecting you to just “row” toward their brilliant vision.

In short, you must understand the context and evaluate whether this phase or its parts are appropriate. We’ll discuss this more later.

Now we move to detailed elaboration of the target solution. Sometimes the rest of the phases are broadly called delivery.

Understanding Users and Their Needs/Values of the Solution. Besides end-users, include other stakeholders who may have wishes or constraints about the solution. But about 90% of this work focuses on users. Of course, staying consistent with the “non-waterfall” principle, you’ve already somewhat understood your users before this point — for example, when discussing possible solutions and choosing one (hard to talk about solutions without knowing who they’re for and what they should deliver — i.e., scope). Here, we study users more deeply, categorize them, and clarify exactly what the solution should provide them.

Important: you won’t always have access to actual users. Sometimes a client or even your own creativity substitutes for users. This is not ideal, and you should try to reach at least some users, but circumstances vary — sometimes you must think about users without them. The stage remains necessary, but the nature of the work changes, which we’ll discuss later.

Requirements Development for the Solution. At this stage, you translate what you’ve learned about the solution’s value to users and stakeholders into specific things that must be included in the solution — both functional and non-functional. This is where you write specifications, user stories, and other key artifacts. Likely, you’ve already started this earlier because, again, this is not a waterfall. An experienced analyst documents requirements and team tasks continuously, even during previous stages.

Handoff of Requirements to Development — time to rest? Nope. Get ready to actively or passively participate in development, testing, and delivery. Questions about requirements will come — from the team, client, management, etc. Also, most development is iterative nowadays, so you’ll be working on the next iteration of the solution (to be fair, this is a new mini-waterfall starting with discovery or requirements for that iteration).

Post-release Support and Operation. After the system (or iteration) is released, your involvement doesn’t vanish. The client, users, and stakeholders will have questions: why isn’t this working right, how should it work, how can we change this because something in the business changed, etc. You help support the operational use of the solution, consulting anyone who needs help understanding it, tracking and processing change requests (when the client realizes too late that something needs changing and pays for it), and participating as a consultant or information conduit in bug fixes (when something was done wrong and the supplier pays for the fix).

Also, add evaluation of the solution — assessing whether the solution helps achieve the desired effect identified during discovery. This is often irrelevant in contract development, where “business value” assessment is out of scope. In product development, it’s more relevant but usually the product manager’s headache rather than the analyst’s. Still, various role combinations exist, so it’s worth mentioning.

This was a high-level overview of typical business analysis stages in an IT project. In future posts, I’ll explore each stage in more detail, discuss practical approaches to tasks within those stages, and highlight popular techniques and tools with links for further study.

As usual, I’m happy to receive any feedback and ideas for future posts. If you want me to focus on specific techniques or tasks — shout out!

As usual, I’m happy to receive any feedback and ideas for future posts. If you want me to focus on specific techniques or tasks — shout out!