Let me clarify right away: this article will intentionally gloss over some of the nuance and precision that a hardcore purist might expect. Yes, I know that BABOK refers to knowledge areas, not activity domains. I understand that the origins of certain terms may differ if you dig through them with the zeal of a historian-archeologist. And sure, some concepts might shift meaning when viewed under the light of a waxing moon on the third Friday of the month. With those caveats out of the way — let’s dive in.

Strategy analysis is a domain of activities focused on identifying the needs of the organization or client and developing a high-level action plan. In other words, before diving into details and bombarding the development team with tomes of specs, the analyst and the client need to understand what big-picture problem they’re trying to solve, what the target solution is, and what its broad components are.

Strategy analysis is a domain of activities focused on identifying the needs of the organization or client and developing a high-level action plan. In other words, before diving into details and bombarding the development team with tomes of specs, the analyst and the client need to understand what big-picture problem they’re trying to solve, what the target solution is, and what its broad components are.

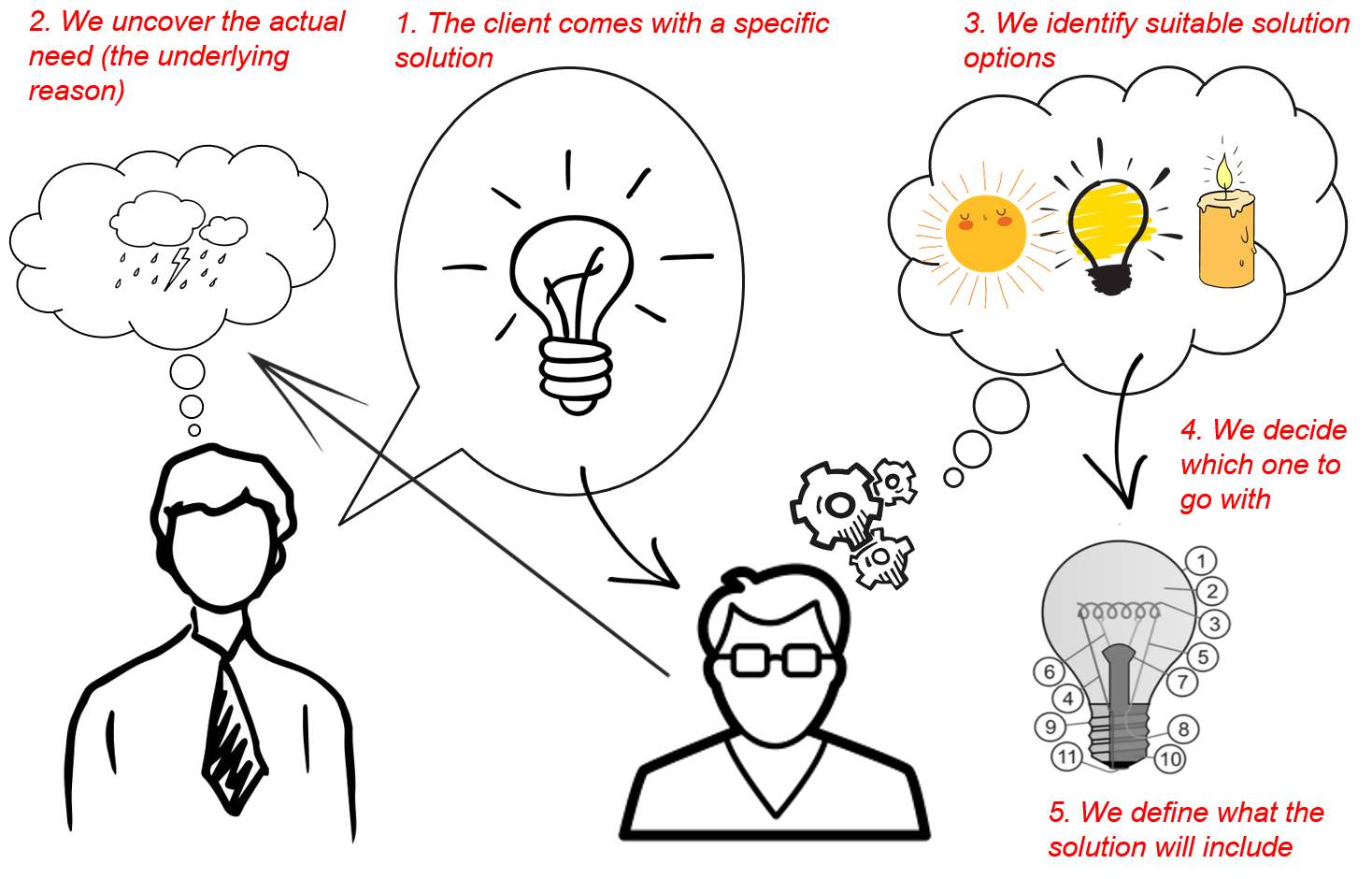

In our training materials, we usually represent the conceptual flow like this:

The fifth point, by the way, can sometimes logically slide between the second and third. Often, to understand the range of potential solutions, you first need to grasp what the content of any of those solutions would likely include.

In practice, people frequently skip one or more of these steps. In some settings, IT analysts don’t even try to uncover the actual reasons behind the client’s request. Elsewhere, teams bypass the solution exploration step entirely and simply take the client's original request at face value. If that’s the working context — and it’s not happening out of ignorance or laziness — then that’s fine. But if an analyst is running the full cycle of this activity, the strategy analysis should yield three key outputs:

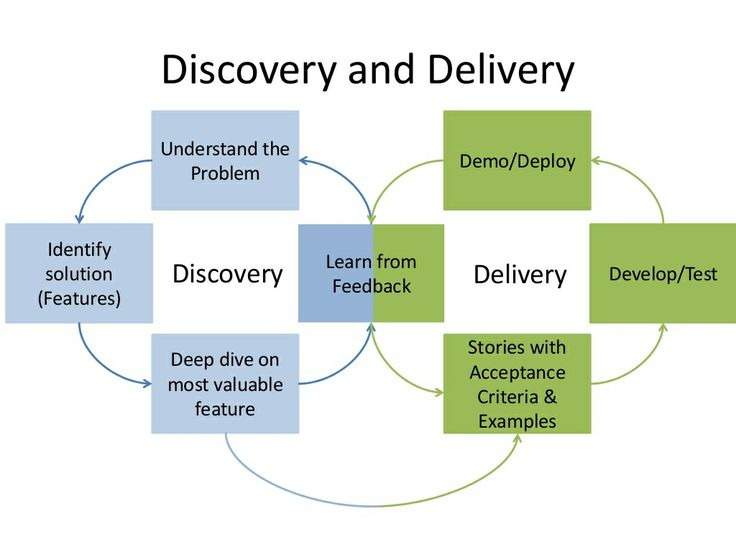

Let’s talk about a trendy term that’s often thrown around these days: discovery. It originally came from either product development or Agile practices — hard to say which exactly — but it’s now commonly used even in client-driven software development. In terms of purpose and content, it’s essentially the same thing as strategy analysis: defining the vision for the solution, its users, goals, and scope. Within this framing, teams often talk about two project phases: discovery and delivery. First, figure out what you're building — then go and build it.

In practice, people frequently skip one or more of these steps. In some settings, IT analysts don’t even try to uncover the actual reasons behind the client’s request. Elsewhere, teams bypass the solution exploration step entirely and simply take the client's original request at face value. If that’s the working context — and it’s not happening out of ignorance or laziness — then that’s fine. But if an analyst is running the full cycle of this activity, the strategy analysis should yield three key outputs:

- Business Requirements (1): Clear goals that serve as direct indicators of whether the client’s or organization’s business needs are being met.

- Solution Vision (2): After evaluating solution options and choosing the most appropriate one, we need to articulate what our target solution is, who it’s intended for, and which of their needs it addresses.

- Solution Scope (3): A high-level overview of what the solution will consist of — essential to understanding the scale of the challenge ahead.

Let’s talk about a trendy term that’s often thrown around these days: discovery. It originally came from either product development or Agile practices — hard to say which exactly — but it’s now commonly used even in client-driven software development. In terms of purpose and content, it’s essentially the same thing as strategy analysis: defining the vision for the solution, its users, goals, and scope. Within this framing, teams often talk about two project phases: discovery and delivery. First, figure out what you're building — then go and build it.

Strategy analysis or Discovery in action. Let’s walk through an example:

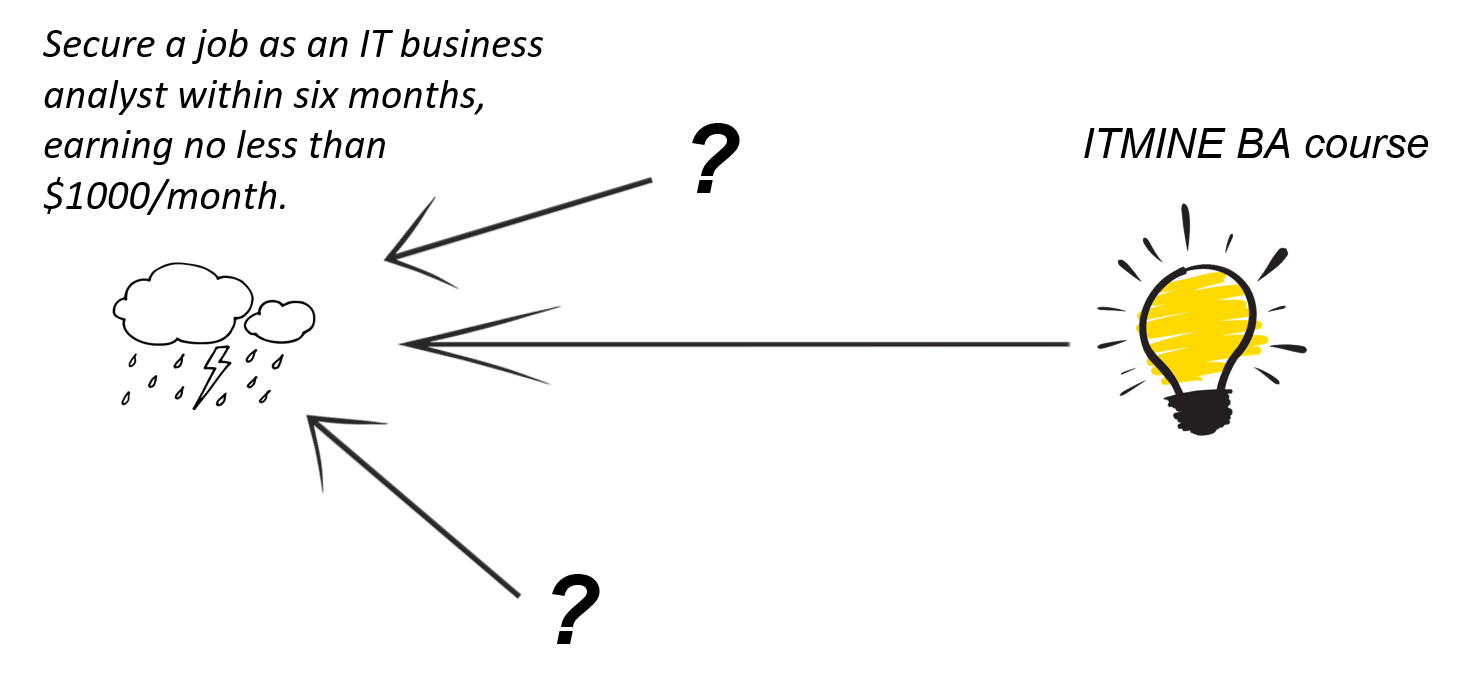

1) A client approaches us to purchase ITMINE’s business analysis course — this is the solution they believe they need.

2) If I’m playing the role of the analyst (which I try to do in such cases), my task is to understand — or help the client uncover — the need behind this solution. Through discussion, we might arrive at something like “I see an opportunity to switch to a more lucrative profession.”

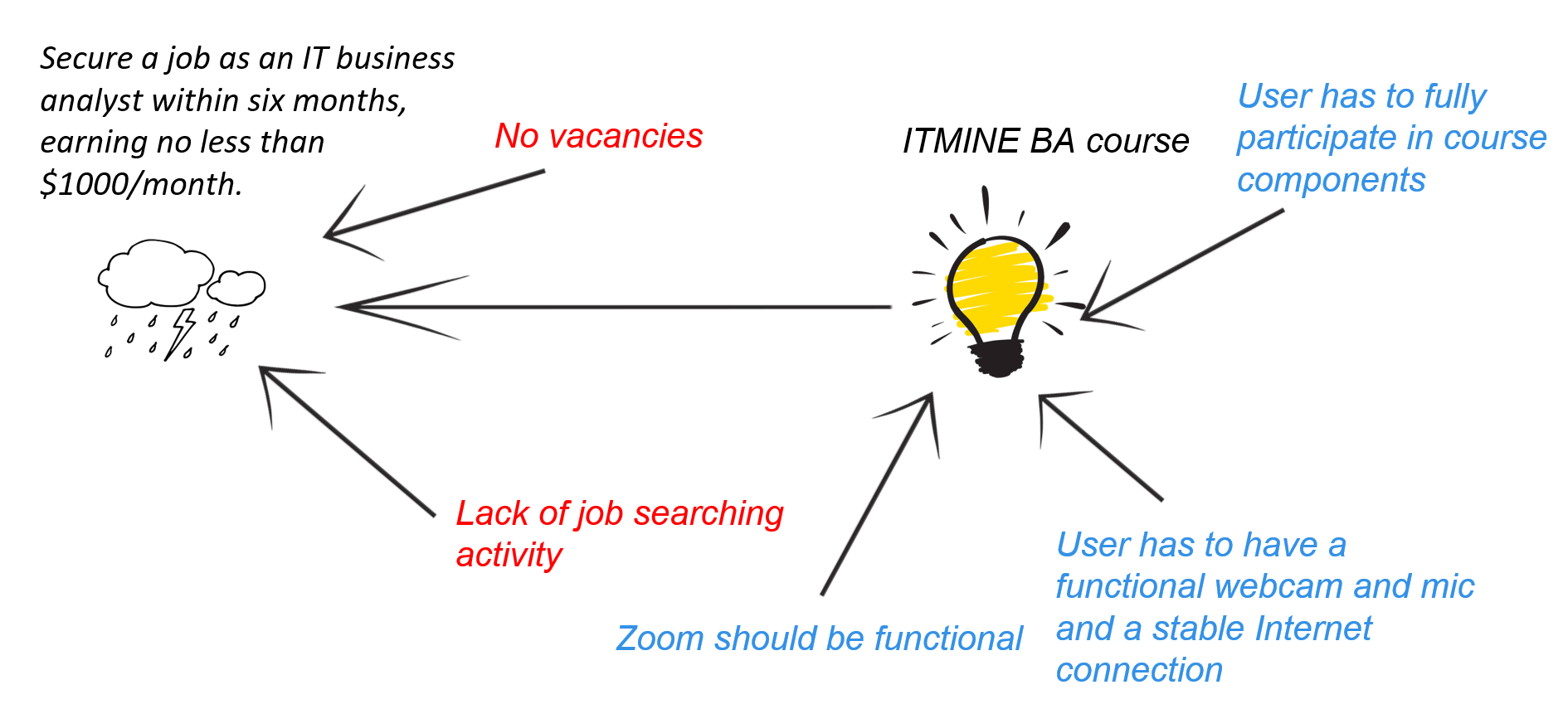

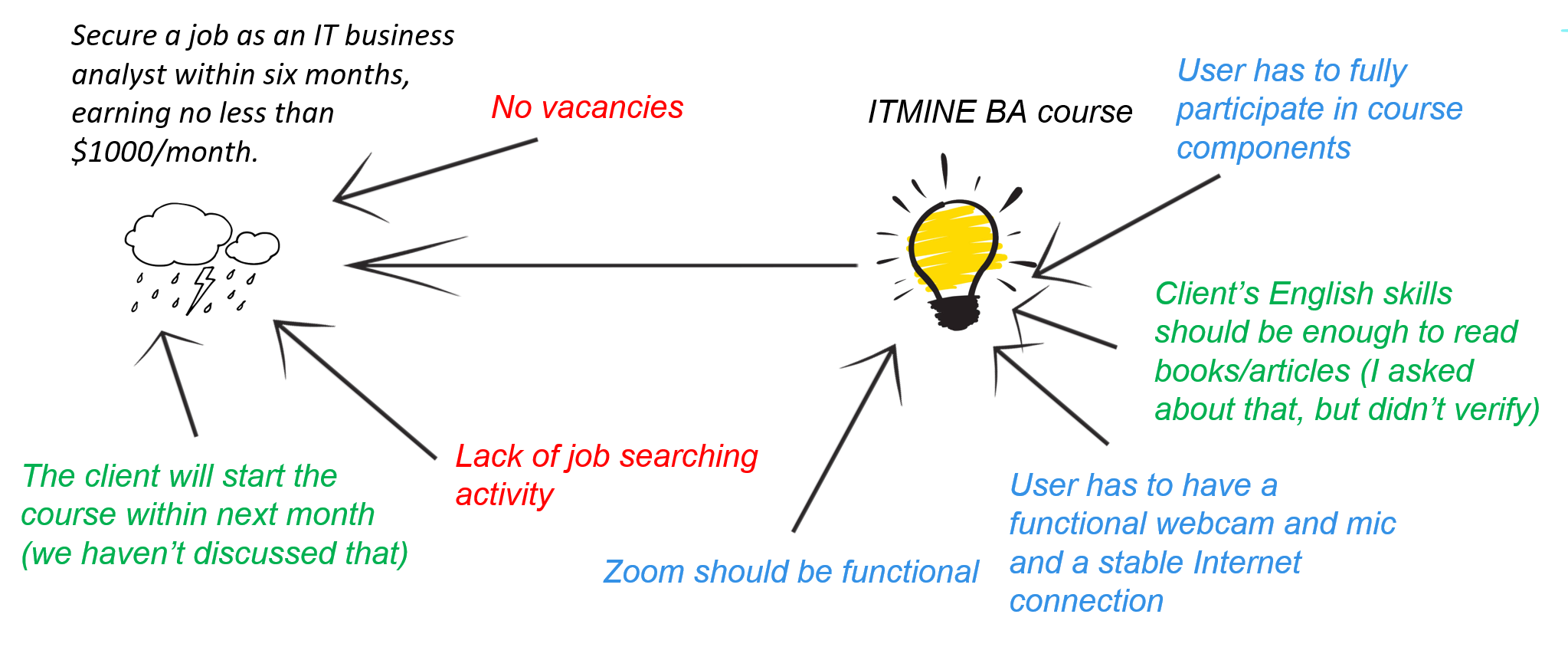

3) What we don’t usually do in a course sales context — but what you should definitely do when working on a real project — is translate that need into a formal business requirement (1). For example, we might define the goal as: “Secure a job as an IT business analyst within six months, earning no less than $1000/month.”

4) Together with the client, we then evaluate whether the original solution is actually the best fit. We try not to anchor ourselves to it without considering alternatives. Here’s a possible set of options (which I help the client brainstorm using either domain expertise or, when that’s lacking, some logical reasoning and lightweight research):

5) Next, we articulate a solution vision (2) that all parties can clearly understand: “The solution is a group-based online course from ITMINE that will equip the client with the knowledge and skills necessary to secure employment as an IT business analyst.”

Of course, we could expand this vision with more informative components, but we’ll stop here for brevity.

6) Solution scope (3): Since the BA course from ITMINE is already a packaged, off-the-shelf solution, there’s no need for custom development or post-sale customization. So in this particular case, defining scope isn’t necessary. Still, for completeness, here’s a high-level breakdown of what the course includes:

And that’s the whole discovery phase. Now both the client and we have a clear understanding of why, what, and how much we’re doing. Of course, for IT projects, the process is more complex and requires eliciting each piece of information through more robust techniques — but again, the goal here is to grasp the core concepts, not conduct a full-blown analysis.

1) A client approaches us to purchase ITMINE’s business analysis course — this is the solution they believe they need.

2) If I’m playing the role of the analyst (which I try to do in such cases), my task is to understand — or help the client uncover — the need behind this solution. Through discussion, we might arrive at something like “I see an opportunity to switch to a more lucrative profession.”

3) What we don’t usually do in a course sales context — but what you should definitely do when working on a real project — is translate that need into a formal business requirement (1). For example, we might define the goal as: “Secure a job as an IT business analyst within six months, earning no less than $1000/month.”

4) Together with the client, we then evaluate whether the original solution is actually the best fit. We try not to anchor ourselves to it without considering alternatives. Here’s a possible set of options (which I help the client brainstorm using either domain expertise or, when that’s lacking, some logical reasoning and lightweight research):

- Self-study

- Working with a personal mentor

- Taking a course

5) Next, we articulate a solution vision (2) that all parties can clearly understand: “The solution is a group-based online course from ITMINE that will equip the client with the knowledge and skills necessary to secure employment as an IT business analyst.”

Of course, we could expand this vision with more informative components, but we’ll stop here for brevity.

6) Solution scope (3): Since the BA course from ITMINE is already a packaged, off-the-shelf solution, there’s no need for custom development or post-sale customization. So in this particular case, defining scope isn’t necessary. Still, for completeness, here’s a high-level breakdown of what the course includes:

- Live training sessions

- Slidecasts covering theory

- Quizzes

- Supplementary reading

- Home practice

- A final mock interview

And that’s the whole discovery phase. Now both the client and we have a clear understanding of why, what, and how much we’re doing. Of course, for IT projects, the process is more complex and requires eliciting each piece of information through more robust techniques — but again, the goal here is to grasp the core concepts, not conduct a full-blown analysis.

Let’s now take a look at Vision and Scope, a key artifact that encapsulates the outputs of strategy analysis. By “artifact,” I don’t necessarily mean a formal document, so no need for Agile purists to tense up — it’s simply a collection of information, which can be captured in a doc, a note-taking tool, or any other format that works for your team.

As you’ve probably gathered, Vision and Scope includes all of the key components discussed above — but not just those. There are a number of additional sections that help clarify and enrich the information. I recommend the following structure, which is based on a popular template originally proposed by Karl Wiegers:

As you’ve probably gathered, Vision and Scope includes all of the key components discussed above — but not just those. There are a number of additional sections that help clarify and enrich the information. I recommend the following structure, which is based on a popular template originally proposed by Karl Wiegers:

1. Business Requirements

1.1. Background and Business Needs

1.2. Business Goals and Success Metrics

2. Solution Vision

2.1. Solution Options

2.2. Vision Statement

2.3. Business Risks

2.4. Business Assumptions and Dependencies

3. Solution Scope and Limitations

3.1. Major Features and Characteristics

3.2. Scope of Initial Release

3.3. Scope of Subsequent Releases

3.4. Limitations and Exclusions

4. Business Context

4.1. Stakeholder Profiles

4.2. Deployment Considerations

1.1. Background and Business Needs

1.2. Business Goals and Success Metrics

2. Solution Vision

2.1. Solution Options

2.2. Vision Statement

2.3. Business Risks

2.4. Business Assumptions and Dependencies

3. Solution Scope and Limitations

3.1. Major Features and Characteristics

3.2. Scope of Initial Release

3.3. Scope of Subsequent Releases

3.4. Limitations and Exclusions

4. Business Context

4.1. Stakeholder Profiles

4.2. Deployment Considerations

We’ll briefly discuss each section next, which will also help deepen your understanding of strategy analysis and the kind of information that’s most useful at this stage.

1. Business Requirements — the section whose ultimate goal is to formulate business requirements — the first key piece of information that matters at the end of strategy analysis. Here, we answer the question: “Why?”

1.1. Background and Business Needs

In this part, we describe the organization’s business needs and the context that gave rise to them — what’s going wrong, where the roots of the problem or opportunity lie, how key related processes function. Our goal by the end of this step is to clearly articulate the problems or opportunities the organization or client is facing.

1.2. Business Goals and Success Metrics

Here, we formulate business requirements based on the identified needs. Typically, these are expressed in the form of business goals. It’s important to understand that we’re not talking about the organization's global business objectives, but rather the goals connected to the change (as defined in BABOK) that the solution is meant to support.

1.1. Background and Business Needs

In this part, we describe the organization’s business needs and the context that gave rise to them — what’s going wrong, where the roots of the problem or opportunity lie, how key related processes function. Our goal by the end of this step is to clearly articulate the problems or opportunities the organization or client is facing.

1.2. Business Goals and Success Metrics

Here, we formulate business requirements based on the identified needs. Typically, these are expressed in the form of business goals. It’s important to understand that we’re not talking about the organization's global business objectives, but rather the goals connected to the change (as defined in BABOK) that the solution is meant to support.

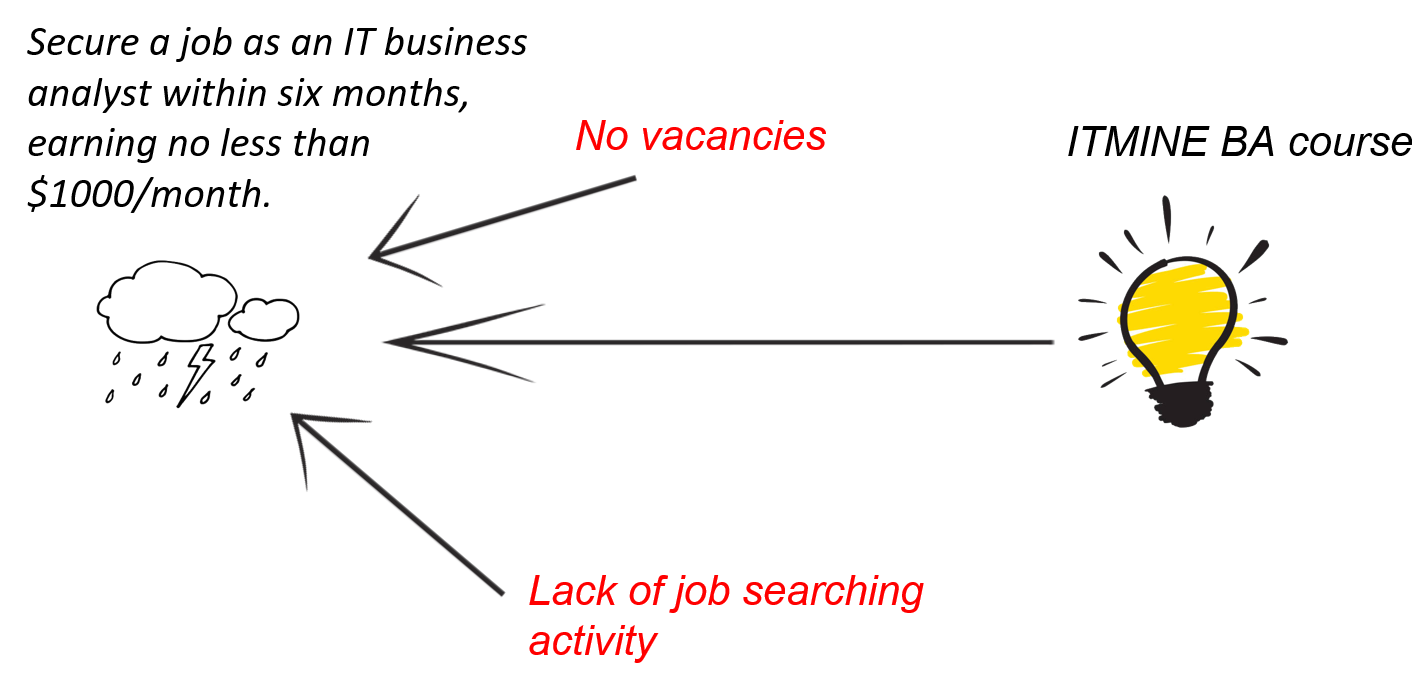

What are Success Metrics? Very often, there’s a gulf between the business goals and the solution intended to achieve them:

In other words, we can't always create a simple cause-and-effect chain like: “If we implement the solution, the goal will be achieved.” There are plenty of other factors influencing whether or not the goal is reached. For example, as a course creator, I can't guarantee that completing an ITMINE course = landing an IT BA job within six months with a salary of at least $1000. We’ll talk more about these factors later. For now, it’s helpful to define success criteria for the solution — indicators that, over time, can show whether the solution is helping the organization progress toward its business goals. How do we, as solution providers, know that we’ve done everything right within our zone of responsibility? One example of a success metric I might use: “Complete the course with a final score of at least 70%.” For me, that’s a sign that the solution is contributing effectively toward the business goal. If the metric isn’t met, the course might not actually help the user — in which case, we need to rethink either the solution itself or how it's being used.

Are success metrics mandatory? No — if there’s no significant gap between the goal and the solution (i.e., no major external context or risk factors that could interfere), then you don’t need to force metrics for the sake of it.

Are success metrics mandatory? No — if there’s no significant gap between the goal and the solution (i.e., no major external context or risk factors that could interfere), then you don’t need to force metrics for the sake of it.

2. Solution Vision — what solution options exist, and which one we’re choosing. Here, we answer: “What?”

2.1. Solution Options

If relevant to the project, this is where we describe and compare the solution options that were discussed.

2.2. Vision Statement

Here, we define the vision for the selected solution.

2.3. Business Risks

Business risks are one of those “question marks” shown earlier in the article, and it’s worth thinking them through together with the client. These are the things that might go wrong even if we have a fully developed and functional solution — in other words, risks on the organization’s side. As we said, implementing a solution is rarely the only factor that determines success. So, what else could affect the outcome, and how?

2.1. Solution Options

If relevant to the project, this is where we describe and compare the solution options that were discussed.

2.2. Vision Statement

Here, we define the vision for the selected solution.

2.3. Business Risks

Business risks are one of those “question marks” shown earlier in the article, and it’s worth thinking them through together with the client. These are the things that might go wrong even if we have a fully developed and functional solution — in other words, risks on the organization’s side. As we said, implementing a solution is rarely the only factor that determines success. So, what else could affect the outcome, and how?

What does the client gain from this step?

2.4. Business Assumptions and Dependencies

This section closely relates to business risks, since it's also about external “question marks”.

Let’s start with dependencies:

What external factors does our solution depend on in order to contribute to the business goals?

Risks and dependencies often get lumped together — and that's fine. But here’s a practical distinction to help keep things clear:

- A clear understanding that the solution alone won’t cut it.

- Identification of other factors that could impact goal achievement.

- Evaluation of the significance of those factors (likelihood + impact).

- Recommendations for how to mitigate those risks — ideally discussed together, since we as analysts might not be domain experts, but we can flag the importance of this step and help guide the discussion.

2.4. Business Assumptions and Dependencies

This section closely relates to business risks, since it's also about external “question marks”.

Let’s start with dependencies:

What external factors does our solution depend on in order to contribute to the business goals?

Risks and dependencies often get lumped together — and that's fine. But here’s a practical distinction to help keep things clear:

- Business risks: Potential negative factors on the client side. What could still go wrong in reaching the goal, even if the solution is implemented correctly? Example: There’s a business analysis course — but beyond the course, what might still prevent the learner from landing a job?

- Dependencies: Factors the solution itself depends on to work successfully. What must be in place for the solution to contribute effectively to the goal? Ideally, we’d eliminate all risks and dependencies. Realistically, we can only minimize them.

Now, what are business assumptions? These are assumptions we base other conclusions on during the strategy analysis phase — things we believe to be true but haven’t confirmed as facts.

Why might we need assumptions? Examples:

Why might we need assumptions? Examples:

- Lack of communication (e.g., a key stakeholder has left the company).

- Inability to turn a hypothesis into a verifiable fact (e.g., assuming 15,000 people will install an app).

- Lack of time or willingness to dig deeper (e.g., conducting market research is costly and time-consuming, so we hypothesize that users want our product).

Assumptions are situational. They’re not like risks or dependencies, which objectively exist. You may or may not have assumptions — it depends on how much info you’ve confirmed as fact. We write them down so we can revisit them later. Over time, they may either be confirmed (and thus removed) or disproven (in which case we’ll need to adjust the goal, solution, or scope).

If I were in a 30-minute conversation with a potential client about a future solution, I don't have time to clarify every detail, so I accompany my Vision and Scope document with a clearly highlighted list of assumptions. Why?

- “We assume the business goal is valid, assuming that…”

- “We believe the solution is optimal, based on the assumption that…”

- “This scope element is deemed necessary, assuming that…”

If I were in a 30-minute conversation with a potential client about a future solution, I don't have time to clarify every detail, so I accompany my Vision and Scope document with a clearly highlighted list of assumptions. Why?

- So the client definitely notices and understands these assumptions.

- So I can refer back to them regularly, checking whether new facts have confirmed or disproved them.

So, what unites business risks, dependencies, and assumptions? All three are essentially question marks that could negatively impact solution's ability to meet the business requirements. Also, all three are outside our control. In other words, this is where our jurisdiction ends. Here's the general principle:

We’re responsible for the quality of the solution and the units of scope we commit to. But let’s also work together — and we’ll help facilitate this — to think through:

This way, we cover our bases and offer the client a more thoughtful analysis — not just the classic "we're just the devs, we only write the code" routine.

A side note: sometimes it's genuinely hard to tell whether something is a risk, a dependency, or an assumption. It all depends on how you phrase it and which angle you approach the information from. But at the very least, the logic above gives you a useful checklist. And if you feel like you're drifting into philosophical debates while trying to classify something — stop. Just write it down somewhere.

We’re responsible for the quality of the solution and the units of scope we commit to. But let’s also work together — and we’ll help facilitate this — to think through:

- What business risks exist on the client’s side? If one of them materializes, will it prevent us from reaching the goal?

- What external dependencies affect the solution? If a dependency breaks, it will likely break something in the solution too. Let’s make sure we understand how to mitigate that (if possible).

- What assumptions have we made during strategy analysis? These assumptions underpin our goal, success criteria, solution, scope, and more. Let’s either validate them and turn them into facts (gain confidence), or be aware that if any of them prove false, everything built on them may crumble.

This way, we cover our bases and offer the client a more thoughtful analysis — not just the classic "we're just the devs, we only write the code" routine.

A side note: sometimes it's genuinely hard to tell whether something is a risk, a dependency, or an assumption. It all depends on how you phrase it and which angle you approach the information from. But at the very least, the logic above gives you a useful checklist. And if you feel like you're drifting into philosophical debates while trying to classify something — stop. Just write it down somewhere.

3. Solution Scope and Limitations — what's in the box? This section defines the content of the solution.

3.1. Major Features and Characteristics

This is the scope of the solution itself.

3.2–3.3. Scope of Initial Release / Scope of Subsequent Releases

This applies when the solution will be delivered iteratively. If there's already some clarity on how that might happen, it goes here. Not relevant for a solution like “Business Analysis Course by ITMINE,” since it's a packaged product delivered all at once in a fixed and complete form.

3.4. Limitations and Exclusions

Clarifications that help narrow the interpretation of the scope. These reduce the risk of the client misunderstanding or assuming something we never promised.

Examples:

3.1. Major Features and Characteristics

This is the scope of the solution itself.

3.2–3.3. Scope of Initial Release / Scope of Subsequent Releases

This applies when the solution will be delivered iteratively. If there's already some clarity on how that might happen, it goes here. Not relevant for a solution like “Business Analysis Course by ITMINE,” since it's a packaged product delivered all at once in a fixed and complete form.

3.4. Limitations and Exclusions

Clarifications that help narrow the interpretation of the scope. These reduce the risk of the client misunderstanding or assuming something we never promised.

Examples:

- ITMINE does not guarantee job placement. We’re happy to help if we can, but there are no promises.

- During self-paced practice, the trainer reviews artifacts once. Additional reviews might happen, but that’s up to the trainer.

4. Business Context

Since we've now defined the three key pieces of information, this section provides additional context to help interpret the discovery outcomes.

4.1. Stakeholder Profiles

Stakeholder analysis during discovery is crucial. This is where we record its results:

This analysis informs:

There's no need to elaborate much here — this isn’t a guide on how to conduct stakeholder analysis or write a Vision and Scope document. There are no complex concepts in this section.

Since we've now defined the three key pieces of information, this section provides additional context to help interpret the discovery outcomes.

4.1. Stakeholder Profiles

Stakeholder analysis during discovery is crucial. This is where we record its results:

- Who the stakeholders are.

- How to categorize them.

- Their influence on business goals and the solution.

- Considerations for working with them.

This analysis informs:

- Who the target users are.

- Who might impact the business goal, success criteria, or other key parameters (and thus be sources of business risks or dependencies).

- What content the solution needs (based on stakeholder needs).

There's no need to elaborate much here — this isn’t a guide on how to conduct stakeholder analysis or write a Vision and Scope document. There are no complex concepts in this section.

4.2. Deployment Considerations

What else needs to happen to make the solution actually work in the target environment and bring that much-awaited business joy? Note: This is not about project tasks or deploying the solution into production. That’s a project manager’s headache, not the analyst’s. Instead, this section refers (or at least should be interpreted as referring) to so-called transition requirements — temporary needs that ensure the solution can be properly integrated and used.

Examples include:

In the case of the course, here’s how I’d approach this. The ITMINE course has a fixed scope — detailed earlier and described in Section 3. There were project tasks related to developing the course — those are already done and don’t matter to me as an analyst. My focus is the solution itself. However, when a new group starts the course, you can’t just “drop” the course onto them. You have to:

What else needs to happen to make the solution actually work in the target environment and bring that much-awaited business joy? Note: This is not about project tasks or deploying the solution into production. That’s a project manager’s headache, not the analyst’s. Instead, this section refers (or at least should be interpreted as referring) to so-called transition requirements — temporary needs that ensure the solution can be properly integrated and used.

Examples include:

- Migrating current data into the new system.

- Training users.

- Creating admin accounts.

- Setting up a Google Play page.

In the case of the course, here’s how I’d approach this. The ITMINE course has a fixed scope — detailed earlier and described in Section 3. There were project tasks related to developing the course — those are already done and don’t matter to me as an analyst. My focus is the solution itself. However, when a new group starts the course, you can’t just “drop” the course onto them. You have to:

- Collect Google accounts to grant access to YouTube videos.

- Enroll students in the LMS.

- Send a welcome email with instructions, etc.

And that’s about it. I hope this helped shed light on what strategy analysis aka discovery really is and how an analyst documents it — making “Vision and Scope” seem far less mysterious or intimidating.

As always, I’d love to hear your feedback in the ITMINE channel (https://t.me/itmineba). And don’t neglect strategy analysis in your work — after all, it’s where business analysis begins conceptually.

As always, I’d love to hear your feedback in the ITMINE channel (https://t.me/itmineba). And don’t neglect strategy analysis in your work — after all, it’s where business analysis begins conceptually.