Let’s talk about a classic by Karl Wiegers and Joy Beatty — Software Requirements, Third Edition. I genuinely value this book, its solid theoretical base, and I have great respect for the authors — I still consider it a must-read “bible” for IT analysts working with software requirements. That said, over the years I’ve developed some questions about it, mostly around the classification of requirements and artifacts. Unsurprisingly, I had many more questions about the second edition, which makes me think some of these questions may well be addressed in a future fourth edition (if it ever comes out).

Since this book is often the first touchpoint for people entering the profession, shaping their initial theoretical foundation (and since many also use its requirements templates), I think it’s useful to highlight areas where it could be clearer. To sum up my position: I strongly recommend studying this work, especially for those just starting out in IT business analysis. But if you notice the same inconsistencies I did, keep them in mind as you build your knowledge and apply it in practice. Of course, it’s possible I’ve misread the authors’ intent — if anyone spots flaws in my interpretation, I’ll gladly take the correction.

So, let’s begin.

So, let’s begin.

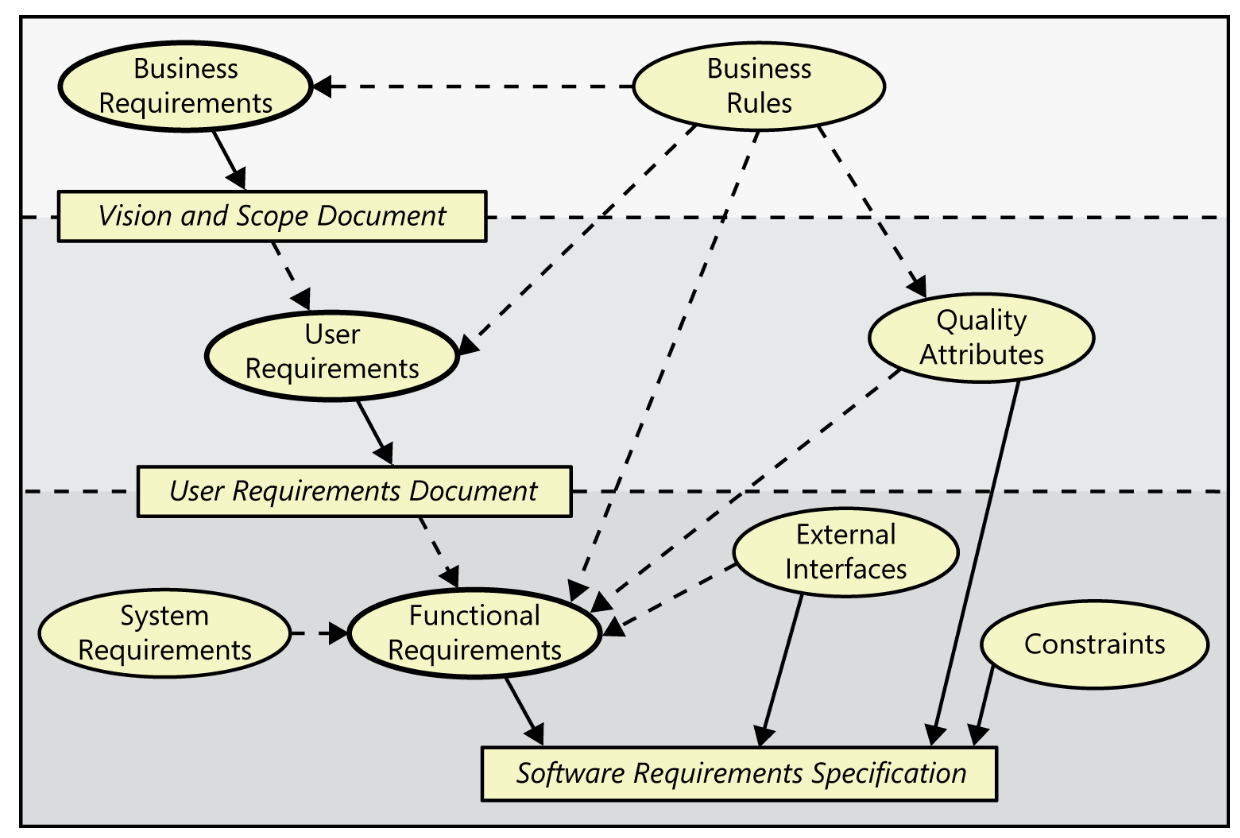

First off: the model includes System requirements.

What’s odd is that the classification is otherwise built around the content of requirements. Business requirements explain why the solution is needed. User requirements capture what users want from it. But then, system requirements suddenly break this logic:

A top-level requirement for a product that contains multiple subsystems, which could be all software or software and hardware.

In other words, the model shifts to a different axis — the level of perspective on the solution. Why try to merge apples and oranges? Business, user, and other types of requirements are equally relevant whether we’re talking about a complex solution, a standalone software, or even a non-software system. A requirement can’t really be classified as either “business” or “system” within this model, because the model mixes two different dimensions:

(a) what the requirement describes, and

(b) what level of solution it targets.

In the framework we use (and advocate), we simply removed “system requirements.” The hierarchy works perfectly well without them — and it’s easier to grasp.

(a) what the requirement describes, and

(b) what level of solution it targets.

In the framework we use (and advocate), we simply removed “system requirements.” The hierarchy works perfectly well without them — and it’s easier to grasp.

Another note: business rules are not requirements (the authors themselves stress this repeatedly). So should they even appear in this model without being clearly separated? In my experience, beginners who skim the diagram often assume business rules are just another type of requirement, which leads to confusion.

User requirements. If we compare this to BABOK (and the overlap between the two models is significant), BABOK uses the term Stakeholder requirements at this level — and I think that’s the better choice. Requirements at this level don’t always come from users alone. The authors themselves admit this:

Some people use the broader term “stakeholder requirements,” to acknowledge the reality that various stakeholders other than direct users will provide requirements. That is certainly true, but we focus the attention at this level on understanding what actual users need to achieve with the help of the product.

The problem is that in practice, if we stick with the term user requirements, we risk narrowing our focus and overlooking important needs. For example:

– developers may have internal requirements (the authors mention this later when discussing internal quality attributes),

– sponsors may demand things like “put our logo on the homepage,” even if they’re not users,

– regulators may impose requirements through business rules.

That’s why I recommend using Stakeholder requirements instead and treating them as such in practice (after proper stakeholder analysis to identify who to involve and why).

– developers may have internal requirements (the authors mention this later when discussing internal quality attributes),

– sponsors may demand things like “put our logo on the homepage,” even if they’re not users,

– regulators may impose requirements through business rules.

That’s why I recommend using Stakeholder requirements instead and treating them as such in practice (after proper stakeholder analysis to identify who to involve and why).

Data requirements. These don’t appear in the model at all. The authors note:

Data requirements are not shown explicitly in this diagram. Functions manipulate data, so data requirements can appear throughout the three levels.

But I don’t see how data requirements could exist across all three levels. What would “data requirements” at the business-requirements level even mean? Business requirements are about business objectives. To me, data requirements belong only at the solution requirements level (more on this below), since they directly specify what information the solution must handle. They should be captured in the SRS or similar artifacts that record solution requirements.

BABOK (3): functional requirements: describe the capabilities that a solution must have in terms of the behaviour and information that the solution will manage.

IREB: Functional requirements concern a result or behavior that shall be provided by a function of a system. This includes requirements for data or the interaction of a system with its environment.

I agree with both. Since functions operate on information, I think it makes sense to split functional requirements into two key groups:

– Behavioral requirements

– Data requirements

– Behavioral requirements

– Data requirements

Solution requirements. This category is missing in the model, though in BABOK it’s the third level of requirements. While that’s not fatal, I find this level rather unclear in the book. The authors write:

Software requirements include three distinct levels: business requirements, user requirements, and functional requirements. In addition, every system has an assortment of nonfunctional requirements.

But why structure it this way? Why are nonfunctional requirements treated differently from functional ones? Why not just group both under a third level called Solution requirements? Why do business rules sit on the same “level” as business requirements (though they can influence all requirement types)? Why do quality attributes appear alongside user requirements (though, like FRs, they must be built into the solution)?

The BABOK model avoids this confusion: the third level is Solution requirements, which consist of FRs and NFRs. That makes it clearer, easier to align with other frameworks, and more practical for separating artifacts (e.g., an SRS that is focused on and contains both FRs and NFRs).

Business Requirements. When it comes to business requirements in the book, I see some contradictions.

The baseline definition seems clear enough:

The baseline definition seems clear enough:

Business requirements describe why the organization is implementing the system — the business benefits the organization hopes to achieve.

I would take it as the foundation (it also aligns with most other sources). But then comes this:

“Business requirements” refers to a set of information that, in the aggregate, describes a need that leads to one or more projects to deliver a solution and the desired ultimate business outcomes. Business opportunities, business objectives, success metrics, and a vision statement make up the business requirements.

Why vision statement? A vision statement describes what our target solution will be, not why the organization needs it.

Two core elements of the business requirements are the vision and the scope.

This complicates things even further. Scope defines the content of the solution (features — functional, characteristics — non-functional, probably use cases or user stories — user reqs). Again, that’s a what, not a why.

My recommendation: keep business requirements limited to what was stated at the beginning — business opportunities, business objectives, and success metrics. A vision statement is not itself a requirement concerning the solution, but rather the definition of the target solution, which all requirements in the model are aimed at.

So it’s useful to keep in mind that not all content of the Vision & Scope document qualifies as business requirements. For example, these sections are important context but not business requirements: background (AS-IS situation), vision statement, business risks, assumptions and dependencies, scope and limitations, stakeholder profiles, project priorities.

This brings us to the section Project priorities in the Vision and Scope document. The authors write elsewhere:

So far we have been discussing requirements that describe properties of a software system to be built. Let’s call those product requirements. Projects certainly do have other expectations and deliverables that are not a part of the software the team implements, but that are necessary to the successful completion of the project as a whole. These are project requirements but not product requirements.

I understand the idea of overlapping domains, but I prefer keeping the theory as simple as possible at the outset, with clear boundaries:

– Analysts focus on the solution (product requirements).

– Project managers focus on the project (project requirements).

– Analysts focus on the solution (product requirements).

– Project managers focus on the project (project requirements).

Which is why I find it odd that the Vision and Scope document (supposed to focus on the solution) suddenly includes project priorities:

…five dimensions of features, quality, schedule, cost, and staff.

Except for “features” (solution scope), the rest are clearly project parameters. Operating them requires project-management knowledge and skills. So I would leave this out of the analyst’s scope of responsibility and their artifacts. In my opinion examples like this belong in the project domain, not business analysis:

– Budget overrun up to 15% acceptable without sponsor review

– Team size is half-time project manager, half-time BA, 3 developers, and 1 tester; additional developer and

half-time tester available if necessary

Transition Requirements. I actually like the concept of transition requirements and see them as necessary. Unfortunately, the authors mention them only briefly. For example, in the SRS “Other requirements” section:

Transition requirements that are necessary for migrating from a previous system to a new one could be included here if they involve software being written (as for data conversion programs), or in the project management plan if they do not (as for training development or delivery).

BABOK treats transition requirements as a distinct category, which I think is the right choice. Forgetting about them can be risky.

Closely related is the Deployment Considerations section of the Vision and Scope document:

Summarize the information and activities that are needed to ensure an effective deployment of the solution into its operating environment.

This is a bit unexpected. Earlier, in their discussion of project requirements, the authors list:

Project requirements include......

- Infrastructure changes needed in the operating environment.

- Requirements and procedures for releasing the product, installing it in the operating environment, configuring it, and testing the installation.

This book does not address these sorts of project requirements further. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t important, just that they are out of scope for our focus on software product requirements development and management.

So why do deployment considerations appear in Vision and Scope? The only way I can reconcile this is if Vision and Scope is intended as a hybrid document, mixing solution and project content.

My recommendation: treat this section as transition requirements instead. That said, I suggest distinguishing between:

– Transition requirements: additional temporary activities/measures needed so the delivered and deployed solution (with its FRs and NFRs) actually provides business/user value. Examples: user training, data migration, user notifications, account creation.

– Project work for delivering the solution: activities inherent to the development/deployment process of the solution with its FRs and NFRs (coding, builds, testing, server setup, production rollout).

The first group is definitely within the analyst’s scope. The second — not so much in my opinion.

– Transition requirements: additional temporary activities/measures needed so the delivered and deployed solution (with its FRs and NFRs) actually provides business/user value. Examples: user training, data migration, user notifications, account creation.

– Project work for delivering the solution: activities inherent to the development/deployment process of the solution with its FRs and NFRs (coding, builds, testing, server setup, production rollout).

The first group is definitely within the analyst’s scope. The second — not so much in my opinion.

Background vs. Business Opportunity. Another minor detail in Vision and Scope: the split between Background and Business Opportunity.

Background: Summarize the rationale and context for the new product or for changes to be made to an existing one. Describe the history or situation that led to the decision to build this product.

Business Opportunity: ....describe the business problem that is being solved or the process being improved...

...describe the business opportunity that exists and the market in which the product will be competing...

Describe the problems that cannot currently be solved without the envisioned solution.

To me, the difference is unclear. I prefer the BABOK concept of Business Need — which may be a problem or an opportunity. Business needs lead to business requirements. They are both part of analyzing the current state (AS-IS) and describe what’s wrong or what improvements are desired. That’s enough; we don’t need two separate sections with overlapping content.

Gaps in the Requirement Types Model. The book’s model of requirement types is strong overall, but when comparing it to actual requirement artifacts, I see mismatches.

Take the SRS Operating Environment section. It’s very important. But what type of requirements are they? If we read "The COS shall operate correctly with the following web browsers: Windows Internet Explorer versions 7, 8, and 9; Firefox versions 12 through 26; Google Chrome (all versions); and Apple Safari versions 4.0 through 8.0". — that is clearly a requirement. Yet it doesn’t map cleanly to the model.

My suggestion: add a “Miscellaneous NFRs” bucket — for all non-functional aspects that don’t fit under quality attributes, external interfaces, or constraints. This would cover operating environment requirements, internationalization/localization (which is also a section in the SRS that doesn't directly map to the requirements types model), and other case-specific items.

Following on that, the book also has an [Other requirements] placeholder for the SRS, with examples like legal/regulatory compliance, installation and startup requirements, logging and monitoring, and so on.

And while I understand that any model is, by definition, imperfect, why not still leave room for such requirements under the label "Miscellaneous NFRs"? We have either FRs or NFRs — these are the only categories for software content. That way, there won’t be any difficulties aligning the model with the artifacts described above.

Finally, a few words about the Characteristics of Excellent Requirements. The set of “qualities” is excellent. However, there are no explanations regarding the limitations of their applicability across different types of requirements. And, as I see it, such limitations do exist.

Let’s dig in (and for those who don’t want to read everything — you can jump straight to the green marker).

Let’s dig in (and for those who don’t want to read everything — you can jump straight to the green marker).

In an ideal world, every individual business, user, functional, and nonfunctional requirement would exhibit the qualities described in the following sections.

Complete — I agree, but: the authors focus on presenting user requirements using use cases, user stories, and event-response tables. At the same time, if we go back to the idea that user requirements should be expanded to stakeholder requirements (and, as the authors briefly mention, include descriptions of product attributes or characteristics important to user satisfaction), questions arise.

In my understanding, user/stakeholder requirements are the initial “wants” (often rough), which are later refined by the analyst into solution requirements (FRs and NFRs). And the term “rough” implies that before being analyzed and transformed into solution requirements, these user requirements cannot be considered high-quality.

Example of a user requirement: The system should allow ordering food during working hours (for an employee food-ordering system). When refined into FRs/NFRs, this becomes, for example, a use case “Order Food”, detailed internally with FRs. But is the original user requirement “complete”? It’s hard for me to say.

In my understanding, user/stakeholder requirements are the initial “wants” (often rough), which are later refined by the analyst into solution requirements (FRs and NFRs). And the term “rough” implies that before being analyzed and transformed into solution requirements, these user requirements cannot be considered high-quality.

Example of a user requirement: The system should allow ordering food during working hours (for an employee food-ordering system). When refined into FRs/NFRs, this becomes, for example, a use case “Order Food”, detailed internally with FRs. But is the original user requirement “complete”? It’s hard for me to say.

Correct — agreed, this is relevant for any requirement and, more generally, for any information handled by an analyst.

Feasible (The requirement can be implemented given the known system capabilities, operational environment, and within project time, budget, and resource constraints). Does this apply to business requirements? According to the ideal “from problems to solution” process, at the stage of developing business requirements, we don’t yet know what our final solution will be. How can a business goal be technically feasible if we don’t know what we are going to build? By the way, for goals, there is the SMART framework, which includes Achievable (for the client within the current business context), which is closer to the truth.

Also, can we assess the feasibility of user requirements? For example, “I want the system to be fast.” Only after it’s refined into an NFR does it become something like “Page load time should not exceed 2 seconds with a local network bandwidth of ≥ 100 Mbps.”

Also, can we assess the feasibility of user requirements? For example, “I want the system to be fast.” Only after it’s refined into an NFR does it become something like “Page load time should not exceed 2 seconds with a local network bandwidth of ≥ 100 Mbps.”

Necessary — applicable to all types of requirements. Business requirements must correspond to the business needs they address, stakeholder requirements must align with business requirements and stakeholder needs, and solution requirements must meet stakeholder requirements.

Prioritized — this is a slightly different issue. There is undeniable value in prioritizing business requirements; it’s also might be relevant for stakeholder requirements. But hardly anyone does something like:

Assign an implementation priority to each functional requirement...

Every acceptance criterion in a user story or every system step in a use case (or any other format describing system behavior) is a functional requirement. Who would bother prioritizing every step for all use cases, and why? Why prioritize design constraints if they just need to be followed? Therefore, a note is needed: each team decides what constitutes a work unit (or backlog item in Agile terms) that should be prioritized (e.g., scope units like features, use cases, user stories or quality attributes).

Unambiguous — again, I agree this is useful for any type of information. But I will refer again to user/stakeholder requirements — these “wants” only gain “quality” when transformed by an analyst into solution requirements (FRs and NFRs).

Verifiable (Can a tester develop tests or apply other techniques to determine whether each requirement has actually been implemented in the product?) Testers are unlikely to verify the achievement of business objectives, and checking raw user-level “wants” (e.g., “I want the system to be fast”) is also questionable. Testers will verify solution requirements.

How I would summarize:

- For business requirements, the SMART acronym is excellent — we can take it as the “ideal set of qualities” for this type of requirement.

- For stakeholder requirements (including user requirements): on one hand, they don’t need high quality if we treat them as raw material and input for solution requirements. On the other hand, the portion formatted as use cases or user stories can be checked against specific quality parameters: for user stories, there’s INVEST; for use cases, I haven’t seen a catchy mnemonic, but classical recommendations exist on how to identify and describe them.

- For solution requirements (FRs and NFRs), the checklist above works, but with caveats. Prioritization is a good example.

Conclusion:

I hope the points I listed above help to internalize the theory from this excellent book and apply it in practice with minor adjustments.

In any case, Software Requirements is an enormous and amazing work. Many thanks to Karl Wiegers and Joy Beatty for it!

I hope the points I listed above help to internalize the theory from this excellent book and apply it in practice with minor adjustments.

In any case, Software Requirements is an enormous and amazing work. Many thanks to Karl Wiegers and Joy Beatty for it!