The goal of the article is to demonstrate how a business analyst can convey functional requirements for a software solution to the development team — with maximum detail, while using the user interface (UI) as the starting point.

Disclaimer: This is a beginner-friendly article — which means it will contain its fair share of philosophically debatable ideas that seasoned BA-jedis love to grumble about over a beer. Still, many things will be deliberately simplified in order to provide practical tools and recommendations. That said, some level of theoretical understanding of business analysis will definitely be required.

Disclaimer: This is a beginner-friendly article — which means it will contain its fair share of philosophically debatable ideas that seasoned BA-jedis love to grumble about over a beer. Still, many things will be deliberately simplified in order to provide practical tools and recommendations. That said, some level of theoretical understanding of business analysis will definitely be required.

Let’s first set the context. What is the ultimate task of a business analyst in our reality? To communicate requirements to the development team. What kind of requirements? Solution requirements — so that the team can build a solution that aligns with the expectations of the client and future users. And what are solution requirements, exactly? They’re the final level in the hierarchy of requirements (for example, the BABOK hierarchy), consisting of functional and non-functional requirements. Let’s put aside non-functional requirements — they are out of scope for this article. Most part (and the most important part) of solution requirements is functional requirements — those that define what capabilities (functions) the system must offer, and the content of those functions. If we break down functional requirements further, one commonly used (though not BABOK-official) perspective suggests they consist of two main components: behavioral/functionality requirements (the core part) and data requirements (secondary, describing the data this behavior operates on). We'll also set aside data requirements for now — they are their own area with separate techniques and approaches.

So, the refined question becomes: what are the possible approaches for documenting the core functional requirements expected from a business analyst?

There are many. If you’re an analyst actively working with requirements, you’ve probably heard of or worked with several of these:

But what if, based on your chosen BA approach, you need to document these requirements as thoroughly as possible? What are your options then? Obviously, this level of detail isn’t always required — but it’s easier to simplify a task you know how to do deeply than to go deep when you only know how to skim the surface, right?

It’s generally accepted that artifacts containing the most detailed requirements are associated with predictive approaches:

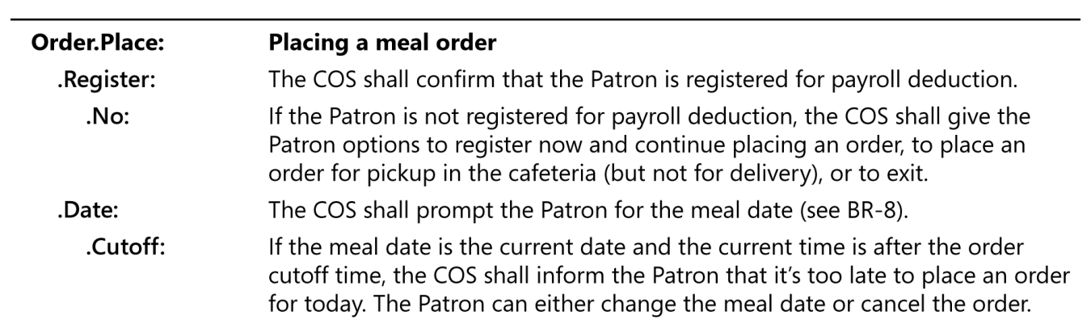

However, the way functional requirements are expressed within such documents can vary greatly, influenced by standards, preferences, and practices. For example, maestro Karl (Mr. Wiegers, that is) suggests writing functional requirements in the SRS like this:

So, the refined question becomes: what are the possible approaches for documenting the core functional requirements expected from a business analyst?

There are many. If you’re an analyst actively working with requirements, you’ve probably heard of or worked with several of these:

- User Stories with acceptance criteria (commonly used in agile/adaptive BA approaches)

- Use Cases with detailed steps

- UI prototypes with textual annotations

- Plain-language descriptions (frequently seen in environments with no mature BA processes)

- ...and so on.

But what if, based on your chosen BA approach, you need to document these requirements as thoroughly as possible? What are your options then? Obviously, this level of detail isn’t always required — but it’s easier to simplify a task you know how to do deeply than to go deep when you only know how to skim the surface, right?

It’s generally accepted that artifacts containing the most detailed requirements are associated with predictive approaches:

- Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

- Functional Specification, and other synonymous terms that essentially describe one thing: a document that outlines detailed solution requirements.

However, the way functional requirements are expressed within such documents can vary greatly, influenced by standards, preferences, and practices. For example, maestro Karl (Mr. Wiegers, that is) suggests writing functional requirements in the SRS like this:

Now, I wouldn’t say this is the most detailed possible approach — but here we bump into a key question every analyst must consider: Who is responsible for UI/UX in your project team?

The user interface and user experience are sometimes part of solution requirements, and sometimes not — depending on the project context. Why is this important? A classic analyst focuses on requirements. They typically avoid diving into implementation details (like database structures, system architecture, etc.). Classic analysts aim to keep requirements at the "what" level, not the "how" — for example, the N in INVEST for user stories insists that stories should capture what is needed, not prescribe how it must be built.

So then — what do we make of UI, with all its forms, fields, dropdowns, and buttons?

The answer depends entirely on the norms in your company/team/project. Typically, if there's a dedicated person who handles UI/UX — and can do it better than you — then UI is not part of the requirements. Instead, it's part of the solution design, and the analyst’s job is to stay UI-free.

The example from Karl Wiegers above shows how to describe requirements without referencing UI. User Stories with a properly maintained "N" follow the same principle. Classic Use Cases do the same — remaining interface-agnostic and implementation-neutral.

But is this always the case in practice? Not really. Often, analysts are responsible for UI design simply because no one on the team is better suited for it. In such situations, integrating UI into the requirements and treating it as part of the requirements specification is totally valid. And this is where I want to share a basic approach that allows you to describe system behavior in almost maximum detail — using the UI as the foundation.

Everything I describe below is primarily aimed at highly detailed artifacts like SRS etc. However, that doesn’t mean this approach is limited to such documents. If you’re a flexible analyst who doesn’t believe in rigid dogma, you can just as well inject this type of content into your User Stories or Jira tickets if it serves your documentation goals.

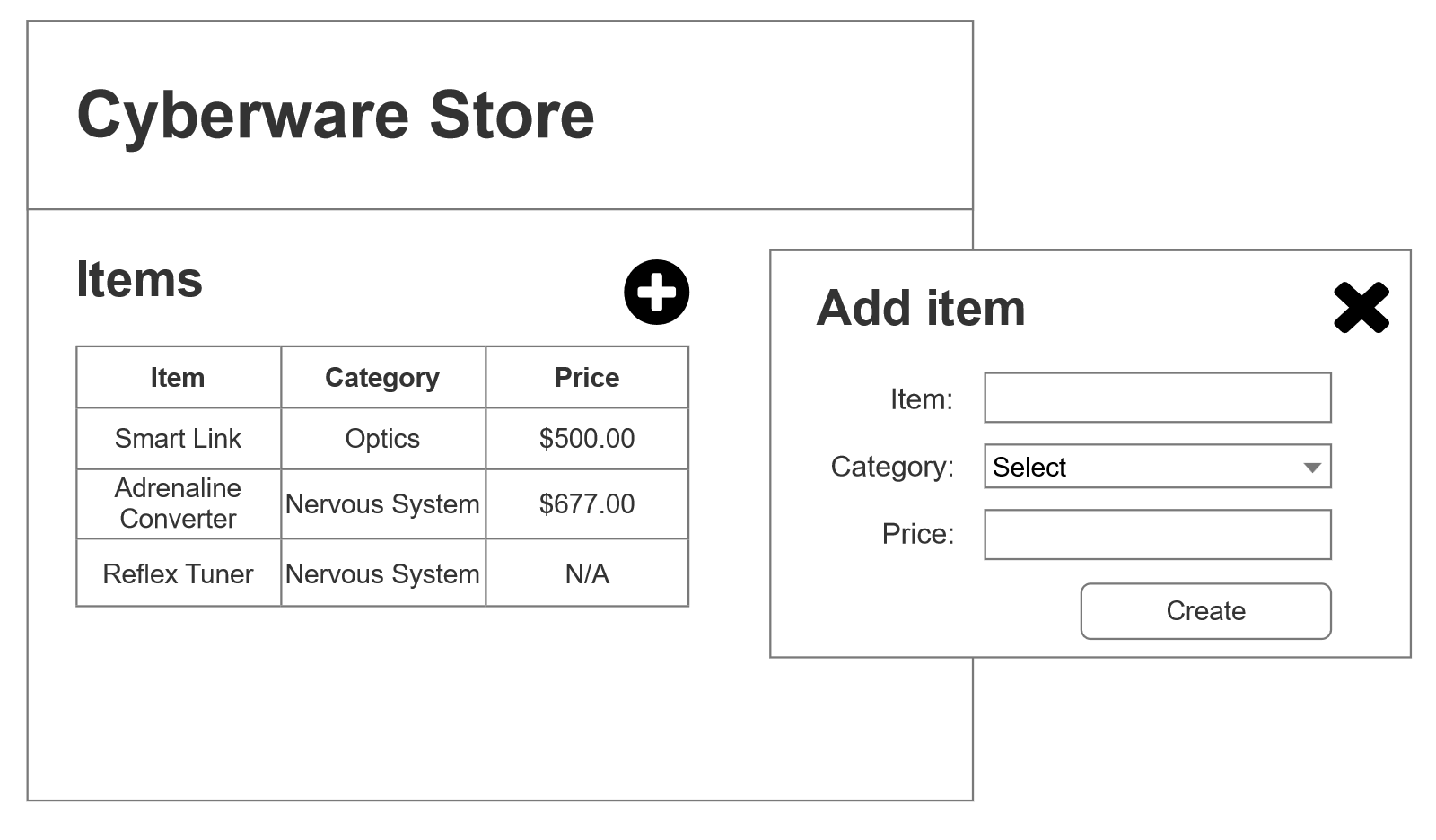

Let’s take a simple example that involves both viewing and entering information into the system. Say we have a basic product catalog with the ability to add a new product — a simple web page for an e-commerce system. From a UI standpoint, our system consists of one page and a pop-up window for adding a new product.

The user interface and user experience are sometimes part of solution requirements, and sometimes not — depending on the project context. Why is this important? A classic analyst focuses on requirements. They typically avoid diving into implementation details (like database structures, system architecture, etc.). Classic analysts aim to keep requirements at the "what" level, not the "how" — for example, the N in INVEST for user stories insists that stories should capture what is needed, not prescribe how it must be built.

So then — what do we make of UI, with all its forms, fields, dropdowns, and buttons?

The answer depends entirely on the norms in your company/team/project. Typically, if there's a dedicated person who handles UI/UX — and can do it better than you — then UI is not part of the requirements. Instead, it's part of the solution design, and the analyst’s job is to stay UI-free.

The example from Karl Wiegers above shows how to describe requirements without referencing UI. User Stories with a properly maintained "N" follow the same principle. Classic Use Cases do the same — remaining interface-agnostic and implementation-neutral.

But is this always the case in practice? Not really. Often, analysts are responsible for UI design simply because no one on the team is better suited for it. In such situations, integrating UI into the requirements and treating it as part of the requirements specification is totally valid. And this is where I want to share a basic approach that allows you to describe system behavior in almost maximum detail — using the UI as the foundation.

Everything I describe below is primarily aimed at highly detailed artifacts like SRS etc. However, that doesn’t mean this approach is limited to such documents. If you’re a flexible analyst who doesn’t believe in rigid dogma, you can just as well inject this type of content into your User Stories or Jira tickets if it serves your documentation goals.

Let’s take a simple example that involves both viewing and entering information into the system. Say we have a basic product catalog with the ability to add a new product — a simple web page for an e-commerce system. From a UI standpoint, our system consists of one page and a pop-up window for adding a new product.

Let’s get back to the methods of documenting behavioral requirements mentioned earlier and briefly recall how you might convey such requirements to the team:

Of course, these aren't the only ways to present requirements — the combinations of techniques, artifacts (i.e., containers), and storage systems are nearly endless. But the ones listed here are the frequently used ones.

My goal here is to demonstrate how requirements can be presented in the context of the last approach on that list — the SRS — and with a focus on UI. So, let’s do that.

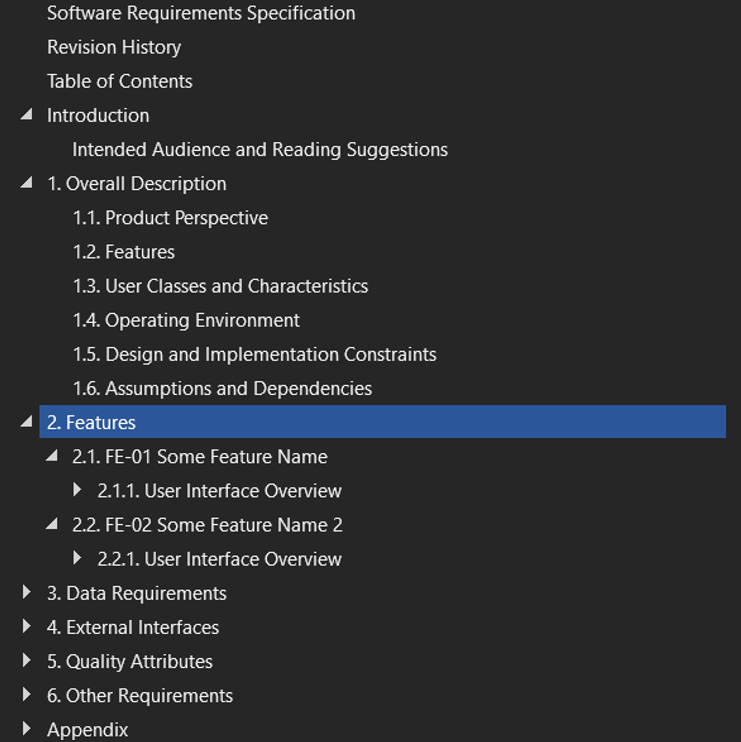

If you're writing an SRS, most templates will include a section named similar to Functional Requirements, which is exactly where your behavioral requirements should go — describing how the system is supposed to act. In terms of document structure, it might look like this:

- Create a set of User Stories (e.g., “Browse Products” and “Add Product”) in Confluence and fill them out with acceptance criteria (in GWT format or any other).

- Do the same using Use Cases instead (e.g., “Browse Products” and “Add a New Product”) with full detail (preconditions, scenarios, and other parameters), and place them wherever you like (like that same Confluence, why not).

- Create a wireframe (as above) and annotate it with textual notes. This is a perfectly valid option for such a “super-complex” system — why overcomplicate things? 😊 Simply attach it to the task in Jira as requirements.

- Compose an SRS following the example from Karl Wiegers’ book above, with all the bells and whistles like a title page, revision history, and other formalities.

Of course, these aren't the only ways to present requirements — the combinations of techniques, artifacts (i.e., containers), and storage systems are nearly endless. But the ones listed here are the frequently used ones.

My goal here is to demonstrate how requirements can be presented in the context of the last approach on that list — the SRS — and with a focus on UI. So, let’s do that.

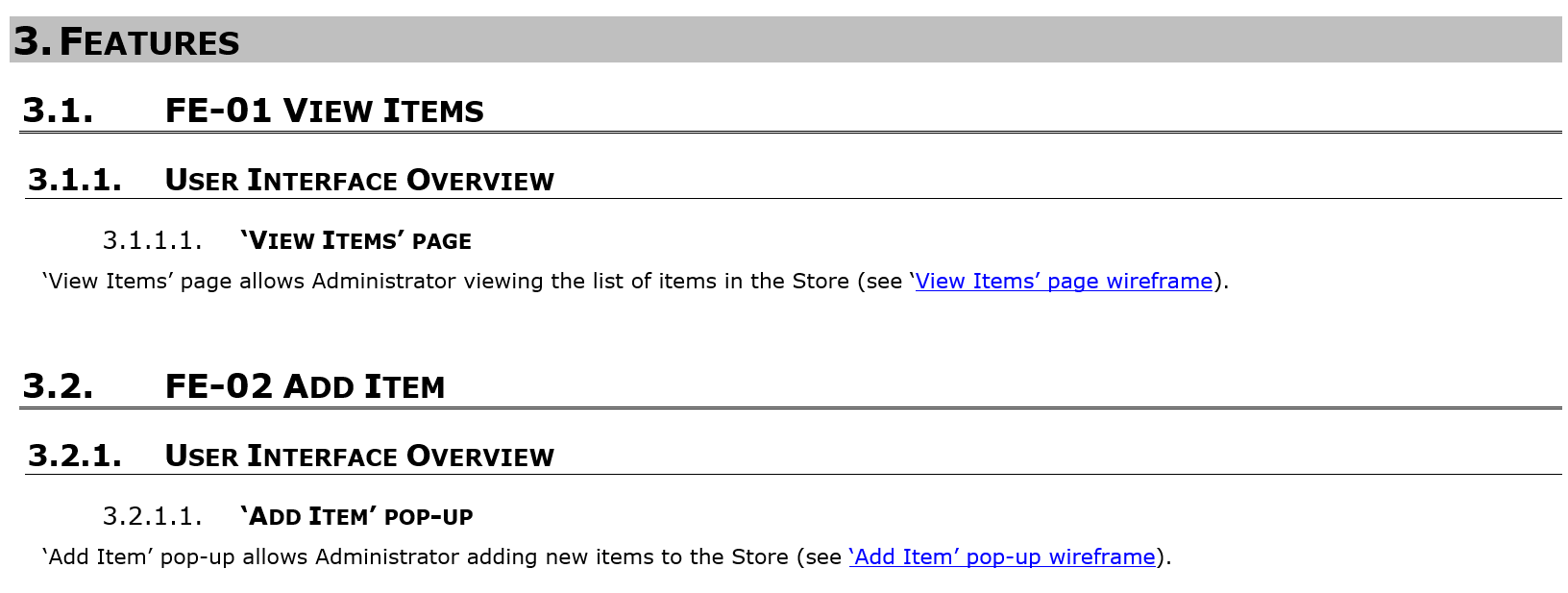

If you're writing an SRS, most templates will include a section named similar to Functional Requirements, which is exactly where your behavioral requirements should go — describing how the system is supposed to act. In terms of document structure, it might look like this:

In this section, it's helpful to group the requirements based on the elements of the solution's scope. These could be features, use cases, or even user stories.

Within each subsection in section 2 (in our example above), there’s a subsection called User Interface Overview — which is where we’ll spend most of our time in this article. Naturally, if you have requirements unrelated to the UI (e.g., email notifications sent by the system), you’d simply rename this section to something else, since the UI would be irrelevant there.

So, what exactly should go into the User Interface Overview section?

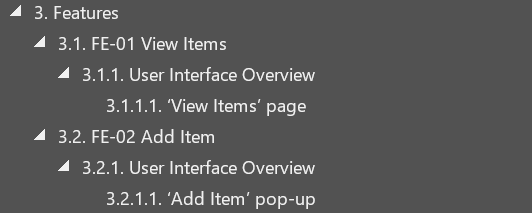

First, identify the key structural elements of your UI (pages, screens, pop-ups, etc.). These will be the backbone for structuring requirements within each feature. Then, map each UI element to its corresponding feature. For example, in our case it might look like this:

Within each subsection in section 2 (in our example above), there’s a subsection called User Interface Overview — which is where we’ll spend most of our time in this article. Naturally, if you have requirements unrelated to the UI (e.g., email notifications sent by the system), you’d simply rename this section to something else, since the UI would be irrelevant there.

So, what exactly should go into the User Interface Overview section?

First, identify the key structural elements of your UI (pages, screens, pop-ups, etc.). These will be the backbone for structuring requirements within each feature. Then, map each UI element to its corresponding feature. For example, in our case it might look like this:

Once that’s done, all that’s left is to fill in the content for each subsection. Sounds simple, right? 😊

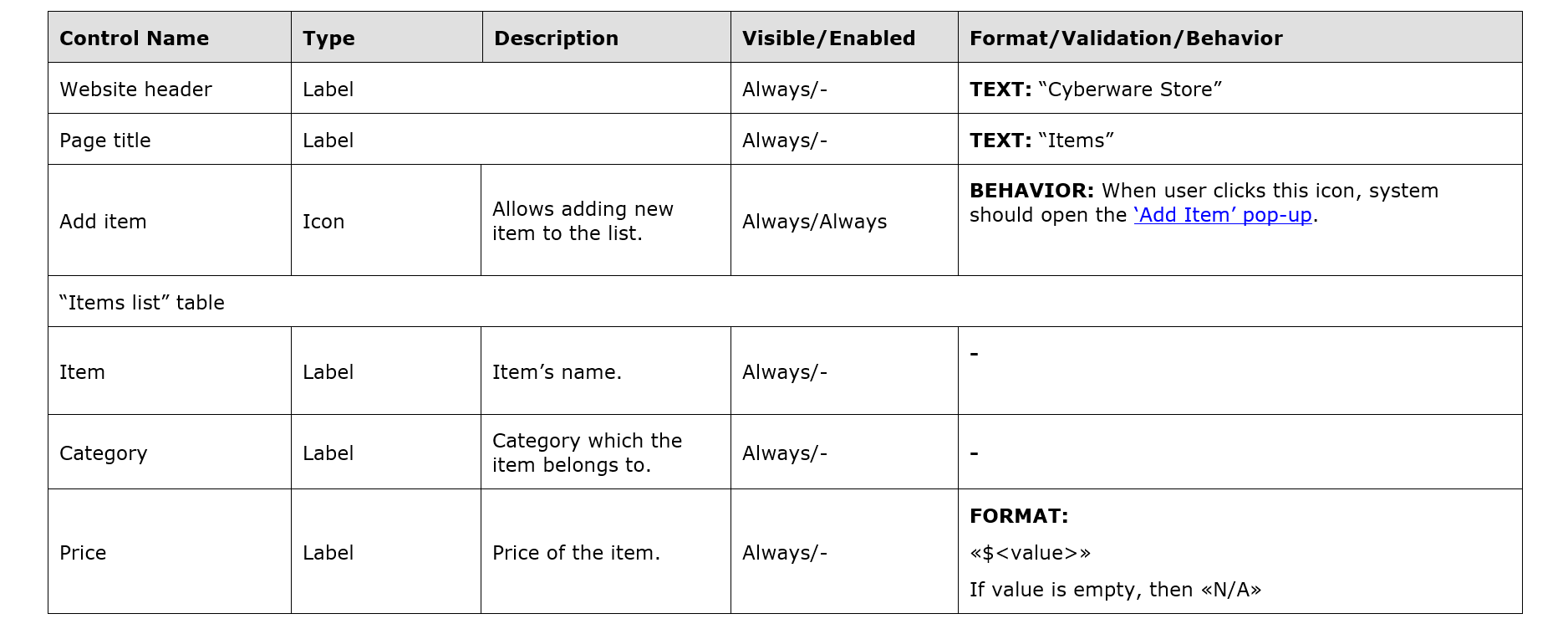

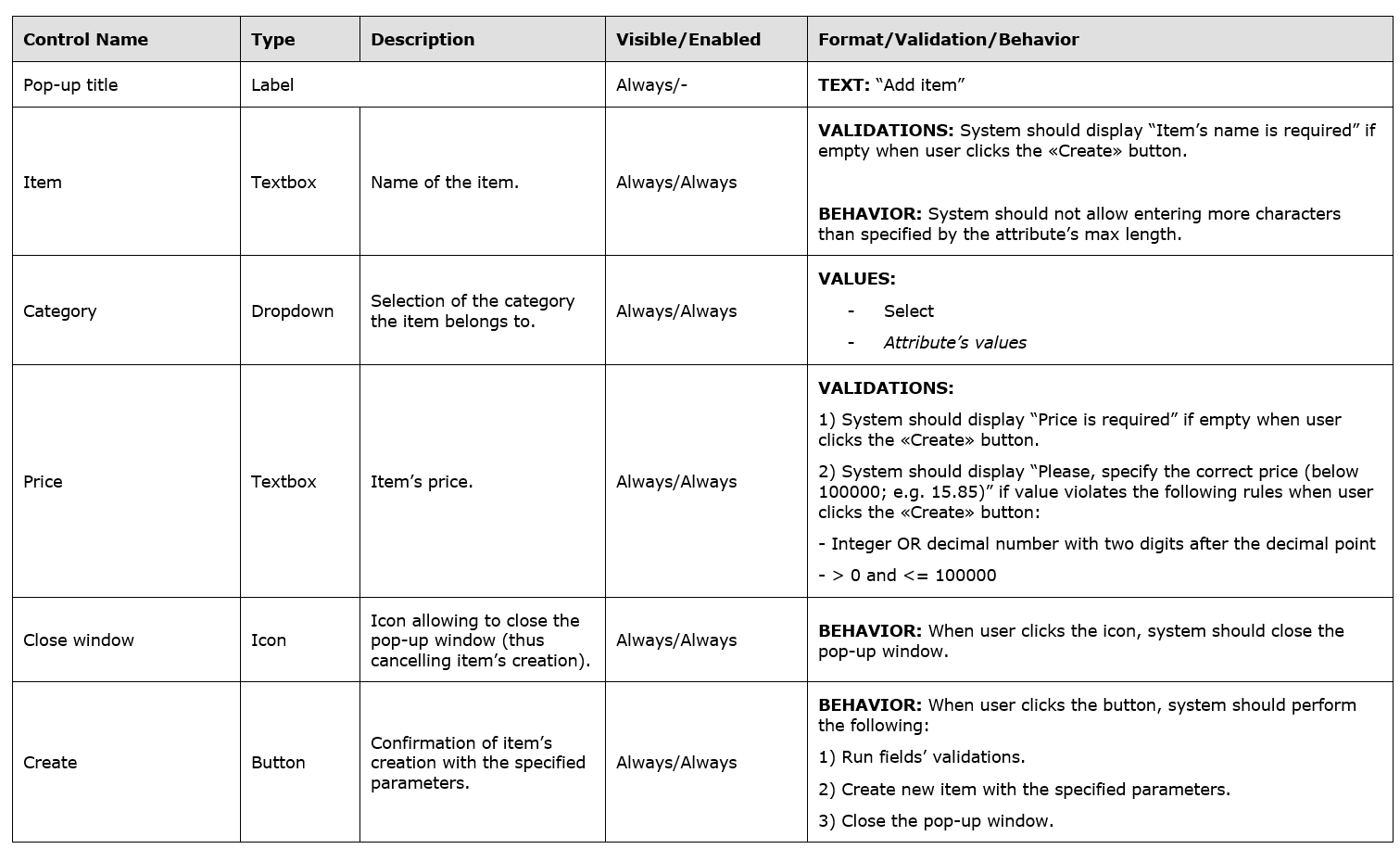

Start with a brief description of what the UI element is and what it’s for. Here, you can also show (or link to) a wireframe to help readers visualize the set of controls it contains and how they're laid out.

Start with a brief description of what the UI element is and what it’s for. Here, you can also show (or link to) a wireframe to help readers visualize the set of controls it contains and how they're laid out.

Next comes the real work: you’ll need to describe the requirements for the UI blocks (if any) and the individual controls in a table. Every type of control has its own nuances that need to be accounted for, so early on, I suggest keeping a checklist or even embedding one in your SRS template that reminds you of what aspects to consider, clarify, and describe for each control type. As you gain experience, you’ll naturally start adjusting the level of detail — sometimes skipping some aspects or emphasizing others — and for rare or custom controls, you’ll develop a sense of what’s worth specifying to ensure the team has all the necessary input for implementation.

Below, I’ll provide a sample table filled out for the controls in our example, and I’ll also briefly explain what aspects to keep in mind for commonly used control types not covered in the example.

Here’s what your table should include:

1) Control Name — I recommend using the exact label that will appear next to or inside the control (if there is one). That way, you won’t need to document the labels separately.

Important: If you're specifying data requirements (the second key part of functional requirements, complementing behavioral ones), and I definitely recommend it, the element name can also serve as a link to the associated data attribute described in the Data Requirements section. Most controls are either displaying or collecting data. For instance, when you look at the Item textbox in the Add Item pop-up, it’s meant to input the name of the item into the system. Likewise, the first column in the Items list table displays the same name. This implies there's an Item data entity somewhere in the system that includes an attribute called Name, among others. Different UI elements either display or allow input of this data.

2) Type — Identify what kind of control it is. It’s assumed you’re familiar with the basics of UI design and prototyping, so we won’t go over the full range here.

3) Description — Briefly describe the purpose of the control from the user’s perspective. If it’s obvious, feel free to skip it.

4) Visibility and Availability — Depending on user roles or system states, certain controls (or entire blocks) might be visible or hidden, enabled or disabled. This applies mainly to interactive controls. For example, you might disable a field until the user fills in a previous one. Capture such specifics here.

5) Format, Validation, Behavior, and Other Key Aspects — This is where most of the functional requirements related to UI controls go. You can split this into multiple columns if you prefer. Here’s what to consider:

1) Control Name — I recommend using the exact label that will appear next to or inside the control (if there is one). That way, you won’t need to document the labels separately.

Important: If you're specifying data requirements (the second key part of functional requirements, complementing behavioral ones), and I definitely recommend it, the element name can also serve as a link to the associated data attribute described in the Data Requirements section. Most controls are either displaying or collecting data. For instance, when you look at the Item textbox in the Add Item pop-up, it’s meant to input the name of the item into the system. Likewise, the first column in the Items list table displays the same name. This implies there's an Item data entity somewhere in the system that includes an attribute called Name, among others. Different UI elements either display or allow input of this data.

2) Type — Identify what kind of control it is. It’s assumed you’re familiar with the basics of UI design and prototyping, so we won’t go over the full range here.

3) Description — Briefly describe the purpose of the control from the user’s perspective. If it’s obvious, feel free to skip it.

4) Visibility and Availability — Depending on user roles or system states, certain controls (or entire blocks) might be visible or hidden, enabled or disabled. This applies mainly to interactive controls. For example, you might disable a field until the user fills in a previous one. Capture such specifics here.

5) Format, Validation, Behavior, and Other Key Aspects — This is where most of the functional requirements related to UI controls go. You can split this into multiple columns if you prefer. Here’s what to consider:

- Exact labels' texts

- Validation rules — Specify validations for input controls (text fields, dropdowns, checkboxes, etc.), like mandatory input or format checks. For example, Item, Category, and Price should be validated as required fields, and Price also should be validated for numerical format.

- Controls behavior — Describe what happens when users interact with the control — e.g., clicking a button, selecting a value, losing focus, typing, etc.

- Display/input format — Example: a price entered as a decimal number (e.g., 1000.00) but displayed in the table with a currency symbol or as “N/A” if missing. This level of formatting detail should be captured.

For other controls and other specifics not shown in the example, here’s what to consider:

Again, build your own checklist as you go. If developers ask you for clarification (or worse — if a bug shows up because something was unclear), that’s a sign it should probably go into future requirements.

- Menus: List and order of values, default state

- Links: Target location, open in new window/tab?

- Radio buttons, checkboxes, dropdowns: list of values, default selection, sorting of values in the list

- Text inputs: Input masks, placeholders, default values

- Icons/buttons: Tooltip texts

Again, build your own checklist as you go. If developers ask you for clarification (or worse — if a bug shows up because something was unclear), that’s a sign it should probably go into future requirements.

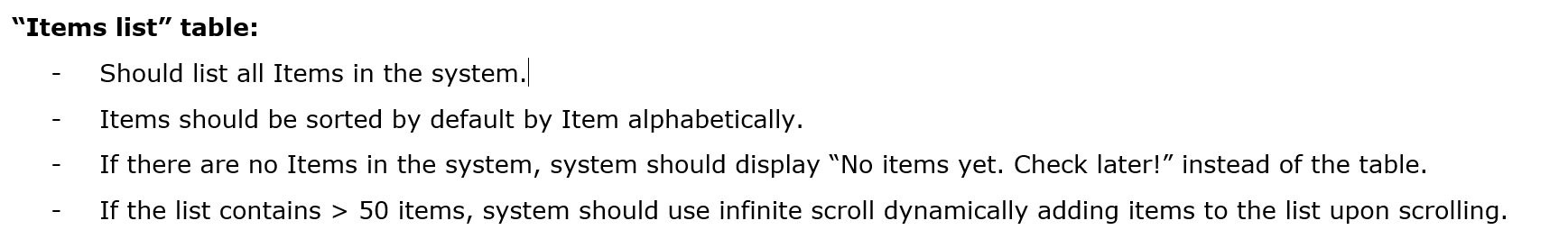

6) Additional Notes. For example, if it’s unclear what exactly to display in a table, spell it out here (and link to the relevant data entity in the Data Dictionary). Let's fix that for our table in the above example:

A couple of final points:

- Controls can be reused across the UI, and as we all know, duplication is bad for maintainability. So document such shared elements once and just link to them.

- Same goes for any other reusable information.

The result? A complete set of functional behavioral requirements based on the UI, leaving minimal room for misinterpretation — which is exactly what a BA often needs when communicating requirements to a dev team.

Of course, as we noted earlier, there are contexts where this approach could be overkill. In mature Agile teams, this kind of rigidity can backfire — remember the Negotiable part of INVEST for user stories? Teams may prefer to co-develop requirements collaboratively, and roles like UX designers or frontend developers may not appreciate strict prescriptive specs. Plus, detailed specs can stifle creativity — some developers prefer a bit of freedom rather than following a step-by-step manual.

But that’s part of broader BA planning and choosing the right documentation strategy.

What we’ve focused on here is how to write detailed behavioral functional requirements tied to UI elements — in case that’s the right tool for the job in your situation.

Of course, as we noted earlier, there are contexts where this approach could be overkill. In mature Agile teams, this kind of rigidity can backfire — remember the Negotiable part of INVEST for user stories? Teams may prefer to co-develop requirements collaboratively, and roles like UX designers or frontend developers may not appreciate strict prescriptive specs. Plus, detailed specs can stifle creativity — some developers prefer a bit of freedom rather than following a step-by-step manual.

But that’s part of broader BA planning and choosing the right documentation strategy.

What we’ve focused on here is how to write detailed behavioral functional requirements tied to UI elements — in case that’s the right tool for the job in your situation.